This week, the lectionary invites us to ponder two gospel selections, both from the Gospel according to Luke. The passages are in Luke 1:26-38 and 46b-55. The English Standard Version (ESV) supplies the passages with the headings “Birth of Jesus Foretold” and “Mary’s Song of Praise: The Magnificat.”

In the first passage, Luke – who was not one of the twelve apostles in Jesus’ inner circle, but a companion of the Apostle Paul[1] – tells of the appearance of the angel Gabriel to Mary. Gabriel told Mary that the Holy Spirit would come upon her; that she would conceive and deliver a child; that he would be called “Son of the Most High;” and that he would “reign over the house of Jacob for ever, and of his kingdom there will be no end.” Centuries ago, Christians called Gabriel’s announcement “the annunciation,” and this appellation continues till this day.

In his preceding paragraphs (verses 8-25), Luke says that this same Gabriel had appeared and spoken to Zechariah six months earlier. Luke adds that Zechariah and his wife Elizabeth were righteous, old, and longed to be parents. Gabriel spoke to Zechariah while he was in the Temple, burning incense and praying in the Holy of Holies – probably the only time in his life. Zechariah’s response was disbelief. He was struck dumb. But what Gabriel said came true. Elizabeth conceived. And delivered. John. John Baptist. The forerunner, the announcer, the promoter of Jesus.

Why did Luke mention Gabriel, while the other gospel writers didn’t? The answer is in Luke’s first lines, in verses 1-4. In these verses, Luke indirectly expresses regret that the other writers, presumably Mark and Matthew, omitted some facts. The evidence is in the phrases “as many have undertaken to compile a narrative,” and “it seemed good to me,” and “to write an orderly account.” These phrases suggest that Luke felt the others missed facts which could make the account more compelling – and awaken or deepen faith. Therefore he, purposefully, wrote another account. An account which conformed to the conventions of biography writing of the time – conventions which placed high value on dream visions and eyewitness accounts, like those of John and Mary’s mothers, and later, of Simeon and Anna.[2],[3]

Luke did more than decide to conform to writing conventions. He decided to evoke episodes from the Bible, God’s Word. He did this by choosing to “demonstrate” the identity of John and of Jesus through the protest dialogues of Zechariah and of Mary with Gabriel. These dialogues make us recall similar, earlier dialogues in the Bible, for example with Abraham,[4] Moses,[5] and Gideon.[6] You can read these in Genesis 17-18, Exodus 6 and Judges 6.

Another thing Luke achieves by placing the two dialogues with Gabriel side-by-side, is that he makes us compare the two dialogues. Zechariah and Elizabeth were old, had prayed for a baby – perhaps partly to be relieved of the cultural shame of being a couple without children. But when God answered their prayer, they were in disbelief. Mary on the other hand, was young, and, knowing her culture would shame her if she became pregnant before marriage, didn’t pray for a baby. But when Gabriel told her she would become pregnant by “the Holy Spirit,” (1:35) before marriage, she didn’t protest. Christians worldwide instantly recognize her response, recorded in Luke 1:38, “… I am the servant of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word.”

I move now to the second part of Mary’s response. As soon as Gabriel left, Mary set off to visit her relative, Elizabeth. While knocking on Elizabeth’s door, Mary shouted out who she was. John Baptist, in Elizabeth’s womb, got excited. Even though he was in the womb, he knew who’d come to visit! Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit. She repeatedly blessed Mary. She referred to Mary as “the mother of my Lord.” And Mary responded with a song which we call The Magnificat, a title inspired by the first line, which reads: My soul magnifies the Lord” (1:46).

Elizabeth saw Mary as the one who would feed, clothe, shelter, protect, and care for the child Jesus, “the Lord.” She described Mary as Jesus’ mother. Luke doesn’t say Elizabeth called Mary “Mother of God.” So why do some people call Mary “Mother of God”?

The simple answer is “because the word ‘Lord’ is often used as an alternate name of God.” But there’s a more elaborate, theological answer. I found it in a 2018 commentary written by Pablo T Gadenz, a Catholic Bible scholar.

According to Gadenz, Elizabeth’s question in verse 43, “why is this granted to me that the mother of my Lord should come to me?” echoes David’s awe during an incident which happened when he began bringing the Ark of God to Jerusalem. It’s in 2 Samuel 6. The Ark was on a cart pulled by oxen.[7] The oxen stumbled. Worried about the Ark, the priest Uzzah, who was driving the cart, put out his hand to steady it. He touched it. God was angry. God struck him dead. David was mad. He said: “How can the ark of the Lord come to me?” This is echoed in Elizabeth’s question.

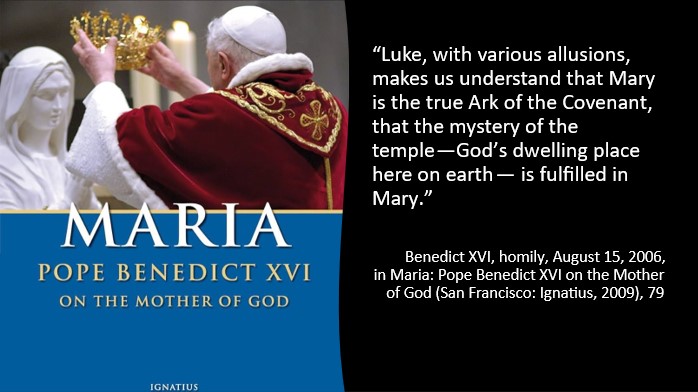

According to Gadenz, Luke wants to show us that Elizabeth was as much in awe of Mary as David was in awe of the Ark. He tells us Luke presents Mary “as the new ark of the covenant, an image or theme similar to her being presented as the new tent of meeting overshadowed by God’s presence (Luke 1:35).” He says Luke “turns up the volume” by choosing to use phrases like “arose and went” which are also found in the Samuel passage and other passages. I do not have space to list them.

Before I conclude, I must point out that another decision or choice of Luke is important. He places the Magnificat in close proximity to the names of tyrant rulers of those times, Herod [the Great] (1:5), Caesar Augustus, Quirinius (2:1-2), Tiberius, Pontius Pilate, Herod [Antipas], Philip, Annas and Caiaphas (3:1-2). Walter Brueggemann reminds us that Luke’s “enumeration of powerful people is not innocent reportage. It is rather a recognition of the way in which the dominant values of society have been arranged according to money and power that depend on violence.” By framing the Magnificat with the names of the tyrant rulers, Luke draws our attention to Mary’s bold, prophetic, dangerous, proclamation that the son she would bear would bring down the most powerful, the most proud, the most corrupt of the land. And cause the humble poor to rejoice. Listen to her politically pregnant words:

51 He has shown strength with his arm;

he has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts;

52 he has brought down the mighty from their thrones

and exalted those of humble estate;

53 he has filled the hungry with good things,

and the rich he has sent away empty.

Now I will conclude.

Why do we join Elizabeth and call Mary blessed? We do so because Mary didn’t allow social norms to stymy her. Because Mary obeyed God. Because though powerless and poor, Mary prophesied the downfall of the powerful. Mary, that teenaged, unwed mother, is the supreme model of faith, of complete trust in God. I end with a quote I found on a Catholic website.

During Christmas 1531, Martin Luther said:

[Mary is the] highest woman and the noblest gem in Christianity after Christ … She is nobility, wisdom, and holiness personified. We can never honour her enough. Still honour and praise must be given to her in such a way as to injure neither Christ nor the Scriptures.

Let us honour Mary by being as faithful as she was. Peace be with you.

[1] Similarly, Mark, who wrote the gospel named for him, was a companion of Peter.

[2] Bible scholar Mikael C Parsons makes a strong case for this in his 2015 Paideia commentary on The Gospel of Luke. In a section titled “The Authorial Audience of Luke” he writes: “cultural scripts and rhetorical conventions are echoed and reconfigured in this new text.” He speaks of Roman progymnasmata, rhetorical exercises which were used to teach the practice of good writing. He adds that Luke used the conventions, to more effectively reject others, for instance, elitism, racism and sexism. Luke’s writing is unmistakably contra mundum, against the world.

[3] Parsons says “… ‘in order’ has little to do with chronological or linear order … ‘in order’ has to do with a rhetorically persuasive presentation.”

[7] Oxen are castrated adult male cattle. Castrated bulls are more docile and therefore safer to work with.

To learn more about Rama, click here.

Pingback: Jesus, Prince of Peace, remover of blindfolds – Bangsar Lutheran Church

Pingback: 25-2 Why did Jesus ask to be baptized? – Bangsar Lutheran Church