In my column titled Why do some people call Mary “Mother of God”? I discussed Mary’s song, The Magnificat. After telling us about the Magnificat, the Gospel according to Luke tells us about the birth of John Baptist and the song of Zechariah, John’s father.

On Christmas day, the lectionary invites us to ponder what Luke tells us next. The verses are in Luke 2:1-14. The English Standard Version helpfully divides the verses into two parts. It supplies the headings “The birth of Jesus Christ” and “The Shepherd and the angels.”

In my Magnificat column, I discussed the origin stories of John Baptist and of Jesus. I explained why Luke included these stories while the other gospel writers did not. I said verses 51-53 are politically pregnant. Here, I’ll expand on why I say the Magnificat is “politically pregnant.”

The Magnificat was voiced by Mary, an unwed, pregnant teenager. She voiced it in the presence of Elizabeth, an old woman who knew Mary had become pregnant, supranaturally. Just as she had. And both were Jews.

There are at least four reasons why the Magnificat is politically pregnant. First, Mary was a Jew. Second, the vast majority of the population were poor, paid oppressive taxes, and got little in return. Third, the words Mary used. And fourth, the choices Luke made when he wrote his gospel. I’ll unpack these four reasons.

First, the Magnificat is politically pregnant because Mary was a Jew.

Jews believe their King should be from the line of David. But the one ruling over them was Herod. Herod was not from the line of David – unlike Joseph, whom Mary was engaged to. Luke stresses the importance of the line of David by telling it to us at the beginning of his gospel (1:26). He emphasizes it by repeating it.

Second, the Magnificat is politically pregnant because the vast majority of the population were poor, paid oppressive taxes, and got little in return.

In 2:1-5, Luke tells us why Jesus was born in Bethlehem. He says it’s because Joseph obeyed a directive of governor Quirinius who imposed an order of Emperor Augustus. The directive required families to return to their hometowns and register their obedience to the emperor by paying a tax.[1] At that time, poverty was rampant. Sakari Hakkinen of the Faculty of Theology in the University of Pretoria provides a good discussion of this in his 2016 paper titled Poverty in the first-century Galilee.

Third, the Magnificat is politically pregnant because of the words Mary used.

In the Magnificat, Mary sang the praises of her son. Her son from the kingly line of David. She used words and themes the emperor used in his self-justifying political propaganda. Biblical scholar N T Wright puts it well:

“Freedom, justice, peace, and salvation were the imperial themes that you could expect to meet in the mass media of the ancient world, that is, on statutes, on coins, in poetry and song and speeches. And the announcement of these themes, focused of course on the person of the emperor who accomplished and guaranteed them, could be spoken of as euangelion, ‘good news/gospel.’”

Fourth, the Magnificat is politically pregnant because of the choices Luke made when he wrote his gospel.

As I said above, Luke named political leaders.[2] He also said – and you’ll find this in verse 14 – the angels announced that the newborn, Jesus, would bring peace on earth – the very thing the Emperor, Caesar Augustus, said he had brought under the so-called pax Romana: a “peace” of a population kept poor by high taxation and constant repression by armed soldiers. And Luke stressed that Jesus had strong Davidic links: he tells us Jesus’ father, Joseph, was from the line of David, and twice says that Jesus was born in the city of David. Like Mary, Luke uses keywords used in the Empire’s political propaganda. Even the word “saviour” had been appropriated by Augustus.[3] The website of the Bibelhaus Museum in Frankfurt puts it succinctly:

The Christ-birth trumps the emperor; the holy gospel is quite different from the imperial ‘gospel’ of bloody victory-peace with which the Roman emperors subjugated the world.

Korean Bible scholar Seyoon Kim, in his incisive book “Christ and Caesar: The Gospel and the Roman Empire in the Writings of Paul and Luke,” reminds us:

Adolf Deissmann, a pioneer of the movement to read Paul in the light of the imperial cult, wrote: “It must not be supposed that St. Paul and his fellow believers went through the world blindfolded, unaffected by what was then moving the minds of men in great cities,” namely, the imperial cult. This famous statement must apply to Luke as much as to Paul.

This Christmas …

Let’s ‘see’ that the Prince of Peace is the King who judges rulers – in our case, Sultans and the Agung – politicians, government ministers, and their propaganda.

Let’s invite Jesus to remove our blindfolds and point us in new directions.

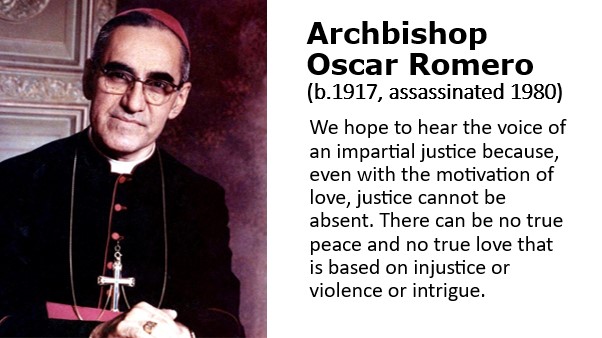

Let’s press for justice, for as Oscar Romero, the martyred Archbishop of El Salvador said in the sermon he gave at the funeral of another martyr, Father Rutilio Grande:

We hope to hear the voice of an impartial justice because, even with the motivation of love, justice cannot be absent. There can be no true peace and no true love that is based on injustice or violence or intrigue.[4]

Peace be with you.

[1] By paying the tax, Jesus’ parents chose not to join a tax revolt led by a resistance group called the Zealots.

[2] Perhaps it was safe for him to do so because he wrote about fifty years after Jesus died.

[3] An Egyptian inscription, called the Priene Calendar Inscription, calls Augustus Caesar a star “shining with the brilliance of the Great Heavenly Savior.” Augustus made emperor worship a normal, mandatory, practice for everyone (link).

[4] 14 March, 1977.

To learn more about Rama, click here.

Pingback: Two more witnesses to Jesus – Bangsar Lutheran Church

Pingback: Just how bad was Herod the Great? – Bangsar Lutheran Church