If you could discuss gender with a person who professes an “alternative gender,” would your views on gender change?

I put myself to the test. But not by discussing with a real-life person. (I am in circles which includes alternative gender persons.) Because that would take too long, would be too scattered, and too hard to evaluate.

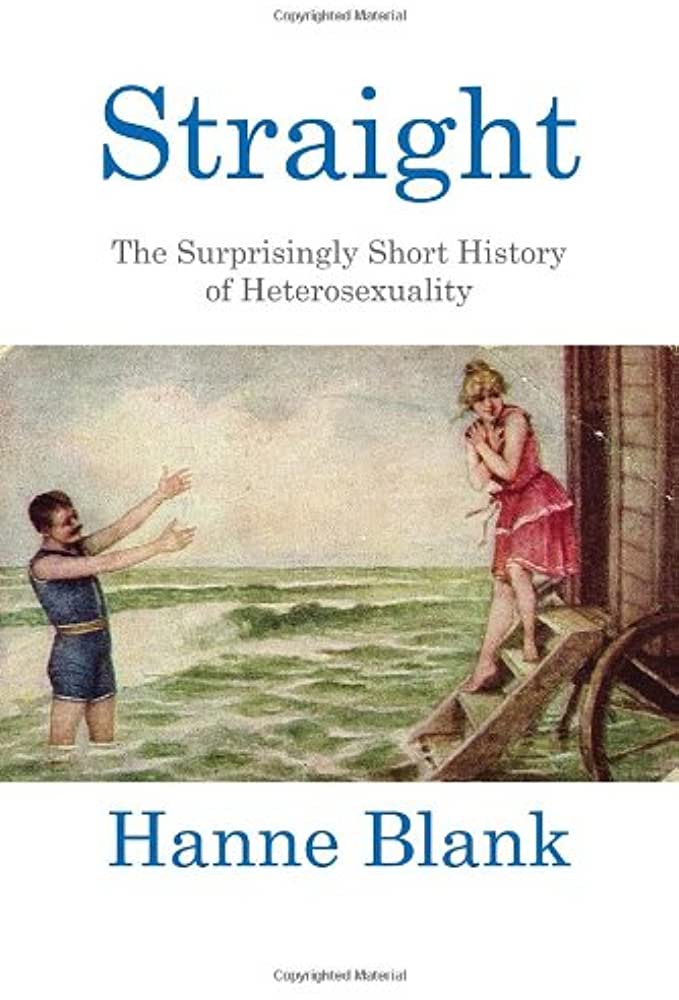

I chose instead to read “Straight: The Surprisingly Short History of Heterosexuality,” 264 pages, by Hanne Blank, an American historian. It was published in 2012 by Beacon Press and received many good reviews.

Hanne Blank’s gender

Blank has a vagina and identifies and expresses herself as female. But she says she’s not sure if she’s heterosexual, because her partner of many years, though equipped with a penis, has an anomaly:

My partner was diagnosed male at birth because he was born with, and indeed still has, a fully functioning penis. But … of the two sex chromosomes—XY—which would be found in the genes of a typical male, and XX, which is the hallmark of the genetically typical female—my partner’s DNA has all three: XXY, a pattern that is simultaneously male, female, and neither. This particular genetic pattern, XXY, is the signature of Kleinfelter Syndrome, one of the most common sex-chromosome anomalies.

Blank is a careful writer. Her choice of “diagnosed” and “anomalies” to describe her partner is calculated and deliberate. She goes on to tell us:

… my partner, like other XXY people who don’t take exogenous hormones, has … little to no facial and body hair, a fine smooth complexion, and a tendency to develop small breasts and slightly rounded hips if he puts on a little weight.

The above extracts are from chapter one. In the last chapter, Blank tells us once she was enraged when a doctor used a female pronoun to address her partner.

I’ve included the above information about Blank to show that the subject of gender is of more than academic interest to her. The subject matters to her personally. She even mentions occasions when she and her partner were threatened because of their seemingly same-sex partnership.

It appears Blank wrote “Straight” in order to try to pin down her thoughts on the subject of gender. And to use her personal stories, considerable wit, and gift of writing, to influence those who think about gender.

Her book gave me much to think about.

What’s in a name?

Blank tells us the words “heterosexual” and “homosexual” were first used in 1868, in Prussia (now Germany), by an activist, to oppose a proposed law to criminalize “unnatural fornication between people and animals, as well as between persons of the male sex.”

That activist, Karl Maria Kertbeny, defined “heterosexuals” as those who are naturally attracted to members of the opposite sex, and “homosexuals” as those who are naturally attracted to members of the same sex.

Blank then tells us how the word “heterosexual” came to signal, worldwide, that sexual attraction to members of the opposite sex is normal, and sexual attraction to members of the same sex is abnormal.

The “how,” was the incorporation, by medical specialists, of the two words into medical language.

According to Blank, the words were forged not to serve science, but to serve repression. According to Blank, “Heterosexual” and “homosexual” are parallel roads in nature. According to Blank, by deft definition, “heterosexuals” were deemed normal, while “homosexuals” were deemed deviant and in need of control by means of laws and policing.

Need of control

Blank says the presumption of need of control arose from three factors which accompanied rapid urbanization – concentration of population, exposure of what was formerly concealed, and lack of social regulation:

… unprecedentedly dense populations transformed urban experience. All sorts of common but unorthodox sexual activities like prostitution, sexual violence, and same-sex eroticism seemed suddenly more frequent, more random, and more out of control than they had been when the cities and their populations were both much smaller. … cities seemed like hotbeds of sexual misconduct and excess. It also appeared to many that people not only engaged in more sexual misconduct in the cities, but that they were more likely to get away with it. … [since] community enforcement of proper behaviour [was] less possible and less likely.

Doxa

Members of majority groups rarely ask questions asked by members of minority people groups. In relation to “sexual” behaviour, Blank asks:

How do we know what we know about sex? How do we arrive at our expectations, our interpretations of words and behaviours and appearances, our opinions of ourselves and of others where sexuality is concerned?

Her answer is “doxa,” a term commonly used by anthropologists. Doxa is:

… the understanding we absorb from our native culture that we use to make sense of the world … absorbing a culture’s doxa … is an inescapable cultural process that starts at birth.

Blank says our doxa of sexuality has been shaped by Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytical theories:

In Freud’s world it was not merely nature or God’s will that made a person sexually “normal.” Upbringing and family were murky, treacherous waters that had to be navigated correctly to arrive at adult heterosexuality’s safe harbour.

and

[In the safe harbour, would be men who had] learned to divert their Oedipal longings for their mothers onto other women, as well as to channel their rampant progenitive desires into more socially acceptable forms of creativity such as architecture and farming. … women, … would have overcome their childhood desires to sleep with their own mothers … and their own fathers … and learned how to desire sex with their husbands in the name of a subconscious desire for children.

Blank says “Disney damage” is another factor which shapes our doxa:

Heterosexual romance, in most of the Disney oeuvre, is necessary to the happy ending. And the happy ending, in the Disney universe, is also the moral of the story: And they all lived happily ever after. The Disney corporation has a long tradition of selling this fantasy of heterosexual romantic bliss to every conceivable audience, starting virtually in the cradle.

Doxa is also shaped by publications, especially of the reports of surveys conducted by Kinsey, and by Masters and Johnson. Consider this:

Kinsey’s orgasm-counting made him a sex-doxa whistle blower. The difference between what people believed the average sex life was like and what it seemed to genuinely be was staggering. But the way Kinsey measured the difference was just as influential as his research. By using orgasms as the beads on his sexological abacus, Kinsey effectively declared that reproduction no longer counted as the baseline of sex between men and women, pleasure did. This had been increasingly true for at least half a century in practice. After Kinsey, it was also true in sexological and biomedical theory. … Kinsey’s orgasm-counting also turned the focus of sex theorizing and research firmly away from moralizing.

Marriage

Blank has much to say about marriage. I’ll keep it short.

Blank points out that once upon a time churches taught that married couples should have intercourse for the sole purpose of making babies. But they okayed intercourse for sexual release or pleasure after the advent of various birth control methods. (She does acknowledge that the Bible, especially in the Song of Songs, celebrates love-making.) Her point is, sex for pleasure is now okay in much Christian teaching.

Blank points out that since the industrial revolution and urbanization, the model of marriage has shifted from “traditional,” a practical alliance between families or communities, to “companionate,” a romantic alliance between two individuals.

Blank points to marriage law reforms which have freed wives from being wards of their husbands. Now, wives can make decisions for themselves:

Vastly wider options for economic, legal, and reproductive autonomy, … meant that women had more ability to decide which, if any, parts of the heterosexual system they wanted to partake of. Women who loved men could do so with or without marriage … Marriage gradually became less of a requirement for forming a household, having and raising a child, and being part of a family. At the same time and for the same reasons, it also became easier for women to express their love of other women. … the horse and carriage of love and marriage had been uncoupled. Love roamed more freely without the bulky carriage in tow.

My response

Blank’s book is about the West and is focused on the USA. But much of our doxa comes from those same places, so we should listen and learn. But our doxa should include biblical, spiritual, and traditional teaching.

Blank doesn’t cover public policy issues which have arisen from the sexual revolution, let alone suggest solutions to them.

Here’s one example: should we stop requiring doctors who deliver babies to register the new-born’s sex – as in some Western countries – and leave it to the child to decide later? (This “solution” may be more acceptable to parents who do not practice circumcision or infant baptism. Smile.)

Here’s another: should we accept that people who are not married can raise babies – regardless of whether they are the babies biological or adoptive parents? (Single parents are very common – even in Malaysia.)

Where do we turn to for answers to such questions? How far do we go with the “parallel roads” formulation of sexuality? Should all such answers be subject to “greater” concerns such as incest and paedophilia?

My response? Asking questions is easy. Listening is relatively easy. Giving persuasive answers is not.

You can read my earlier post on gender here: https://bangsarlutheran.org/what-do-you-think-of-transgender-persons-six-theses/

To learn more about Rama, click here.

Pingback: International Women’s Day 2023. Happy?! ….Or Confused? – Bangsar Lutheran Church