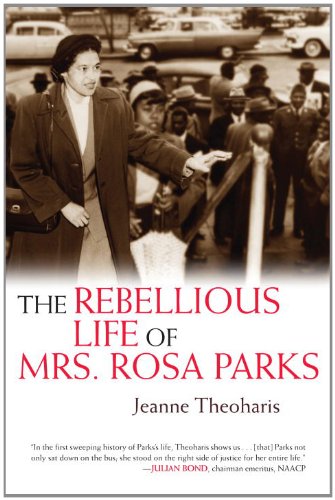

I’ve just finished reading The Rebellious Life of Mrs Rosa Parks, a 2013 book by Professor Jeanne Theoharis, a historian and gifted writer.

Theoharis’ book is a response to things said about Mrs Parks when she died in 2005, two months after Hurricane Katrina. Theoharis believes the US government used Mrs Parks to divert attention from the gross injustices done to blacks before, during and after Hurricane Katrina.

Theoharis’ book is born from anger at the portrayal of Mrs Parks as a one-act person. That act was her refusal to give up her seat on a bus on 1 December 1955. That act resulted in a 13-month boycott by Black people, of buses in Montgomery. That act pulled Dr Martin Luther King Jr into political action.

Theoharis’ book contests the politics of memory which blunts Mrs Parks by presenting her as a gentle seamstress whose tired feet compelled her to remain seated on that day and ignored her role in the events which followed, and her stand against racial discrimination till the day she died.

Theoharis shows instead that Mrs Parks had been an ardent activist long before her bus-seat stand, had a history of refusing to follow the orders of the white bus drivers, well knew the danger her stand on that day posed to her, and intentionally poured her life into the service of justice.

Theoharis shows how difficult Mrs Parks life had been, how much more difficult her life became after her seat-stand, and that she spent over half her life in Detroit, where she continued in activism for several decades.

Theoharis’ book is 320 pages long, and is unputdownable, yet scholarly. Here are a few things I learned from it about Mrs Parks.

Rosa Parks was very poor all her life. As a child, she had tonsilitis. Her mother couldn’t afford the surgery to set it right. She missed a lot of schooldays while her mother saved for the surgery.

Rosa’s grandparents brought her up. Her grandfather believed in self-protection. When there was a chance the Klan might attack, he would sit on the porch from dusk till dawn with his gun. Rosa would sit with him.

Rosa went to an industrial training school funded by a church. To pay her way, she cleaned classrooms. She learned tailoring. She strictly followed rules, was always neat, and was a good student.

Raymond, a barber and activist, courted her. She wasn’t keen on him, but let him win her over. He was the first activist she knew. Raymond worked to support the nine black Scottsboro teenagers who were falsely accused of raping two white women. The support group he formed met in the Parks’ home. When members of the group came for meetings, they put all their guns on the kitchen table. Yes, even then, black people owned guns.

In 1943, wanting to end the injustices Black people faced, Mrs Parks went to a meeting of the local chapter of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Coloured Peoples). She was the only woman there. They asked her to take the minutes. They made her secretary.

Mrs Parks’ brother had served overseas in WWII and was exposed to the same risks as white soldiers. Yet when he returned home in 1945, whites didn’t treat him as an equal. This irked her.

Mrs Parks worked as a seamstress in a store, tailoring suits for white men. Outside her working hours, she worked on cases of injustice. She wrote up cases, drafted press releases, recruited and trained people.

Mrs Parks had been doing such work for a dozen years before her bus-seat stand. She wasn’t the first to make such a stand. (Claudette Colvin, 15-years, had done the same thing, nine months earlier, also in Montgomery.) She hadn’t planned it. She did it because at that moment, she’d had enough of being pushed around. She hadn’t thought about how the gun-carrying bus driver might respond.

Mrs Parks’, four months before her act, at the end of a two-week course on action for social change at Highlander Folk school, said she didn’t think she’d take any action when she got home. Why? Because people weren’t ready.

Police officers, called by the bus driver, arrested Mrs Parks on the bus. The President of the local NAACP, D E Nixon, bailed her out the same day, Friday. She was surprised to see a crowd at the police station when she came out. Nixon persuaded her to see her case through the courts.

Mrs Parks was not part of the women’s group which printed handbills overnight and called for a boycott of buses a couple of days later. On Saturday morning Nixon called Ministers of the local churches to support the boycott, including promoting it during the Sunday sermons.

The boycott leaders didn’t call Rosa to speak at any of the gatherings in Montgomery over the 13 months it lasted. Men dominated. (The boycott ended when the Supreme Court ordered desegregation of the buses.) But she went around the nation making speeches and raising funds.

Mrs Parks lost her job five weeks after her arrest. Raymond lost his job soon thereafter. They couldn’t find work again in Montgomery. The Montgomery Improvement Committee – which managed the boycott – employed others, but not her. The Parks got by with occasional gifts from those who learned of her needs, which she kept to herself.

Mrs Parks worked to care for those affected by the boycott and to keep them motivated. She helped with the massive effort to develop an alternative transportation system using volunteer drivers and their cars. Later, several churches contributed station wagons to the cause.

Mrs Parks received many abusive phone calls and letters and many death threats. Because she was out serving and organizing, it was left to her frail mother, and to Raymond, to field the calls. Raymond became ill and depressed. He turned to drink. It was a very difficult time.

Mrs Parks moved her family to Detroit about eight months after the boycott ended. She got some work as a seamstress, and Raymond as a barber. Their income was even smaller than before. Raymond cared for her mother, as he had in Montgomery, while Rosa continued her activism.

Mrs Parks first got a stable job after about ten years in Detroit when Congressman John Conyers employed her – she had volunteered in his first campaign. The best thing about this job was that it came with health insurance. She worked for Conyers for about twenty years.

Mrs Parks was fond of both Martin Luther King Jr and of Malcolm X. She preferred Malcom’s emphasis on self-protection to Martin’s emphasis on passive resistance. She was also friends with many activists and leaders.

Mrs Parks carried herself very well. People said she was quiet, humble, and elegant. She often prayed and read her Bible. She was a deaconess in her church. In moments of despair, she would turn to the Psalms. (Many leaders of the civil rights movement were Christian Ministers.)

Nelson Mandela honoured Rosa in an amazing way. Theoharis writes:

Four months after Mandela was released, he came to Detroit … Parks had initially not been invited …, but Judge Damon Keith insisted on getting her a place in the receiving line, despite Parks’s embarrassment.

Mandela came off the plane amidst the cheering crowd of dignitaries and well-wishers and froze when he saw Mrs. Parks. Slowly he began walking toward her, chanting “Rosa Parks! Rosa Parks!” The two seasoned freedom fighters embraced.

Rosa had a vision for the world. She loved encouraging the younger generation. She would show up everywhere. She suffered much. I’ll end with this account by Theoharis of what Rosa did in the years before 1955:

“Nixon and Parks were a powerful team. After Alabama’s attorney general publicly claimed federal anti-lynching legislation would only increase lynchings in the state, Nixon went into the office to issue a response—only to find Parks already at work on one.

Every year, they wrote letters to Washington to ask for a federal anti-lynching bill. They persisted, but federal antilynching legislation never passed Congress.

Traveling throughout the state, Rosa Parks sought to document instances of white-on-black brutality in hopes of pursuing legal justice. “Rosa will talk with you” became the understanding throughout Alabama’s black communities.

This work was tiring, and at times demoralizing because most of the cases Parks documented went nowhere.

She issued press releases to the Montgomery Advertiser and Alabama Journal. She forwarded dozens of reports to the NAACP national office documenting suspicious deaths, rapes of black women by white men, instances of voter intimidation, and other incidents of racial injustice.

“It was more a matter of trying to challenge the powers that be,” Parks would later write in her autobiography, “and let it be known that we did not wish to continue being treated as second class citizens.”

I often think we’re too forgetful of people like Rosa Parks. I often think every member of a church should be like Rosa Parks. I often wonder why I’m not.

To learn more about Rama, click here.

Pingback: Reading Romans 5:1-5 during the bus boycott – Bangsar Lutheran Church