The way we think about God and what He expects of us can be fleshed out by the way we think about refugees.

The Bible begins and ends with exiled people. The first book, Genesis, tells of the exile of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. The author of the last book, Revelation, is John, exiled to the island of Patmos. Exiles can’t return to their homelands.

Perhaps the most infamous exile in the Bible is Cain. He was exiled from his land for killing his brother Abel. Though a criminal, he was ‘marked’ by God and protected. (Later, King David too was spared after he killed Uriah.)

God’s choice of means to free the Israelites from their forced labour, and manifold other sufferings in Egypt, was to march them into territories where they became unwelcome foreigners.

Israel’s law, embodied in the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament, made much provision for foreigners. Some have even claimed that the scriptures of no other faith show as much concern for the right treatment of foreigners.

Joseph, the father of Jesus, was told in a dream to become a refugee in Egypt, to flee King Herod who wanted to find and kill Jesus, who, 33 years later, would be crucified as King of the Jews.

Ruth, daughter-in-law of Naomi, was a refugee. She’s one of three women in the genealogy of Jesus (Matthew 1:5). She fled famine in Moab.

We live in a world of refugees. There are two aspects to this. One is at the global level. People leave their countries and head for other countries worldwide, especially from Africa and the Middle East. The second is local. The United Nations has documented about 180,000 refugees in Malaysia.

Those are the documented refugees. To “become documented” as a refugee, a person has to appear at a UNHCR facility and apply to be registered. People fear to appear because exposure could result in actions against them. So, many remain hidden.

There may be up to 4 million undocumented persons in Malaysia. I’ve not seen estimates of how many of these are refugees, people who aren’t safe in their home countries for reasons of ethnicity, religion, nationality, gender orientation, or political opinion.

Locally, even registered refugees dread encounters with police, RELA (a uniformed government-organized volunteer force), and immigration officers. Why? Because there are many stories of these officers extracting bribes from refugees, using threats to arrest them.

Locally, the biggest fear of a refugee is ADD: Arrest. Detention. Deportation. Detention means being in a crowded cell for a minimum of fourteen days, becoming food for bedbugs, being given ‘food even animals reject.’ Some detainees have been incarcerated for years.

Locally, refugees often can’t find or afford medical attention. They sometimes wonder “when one of us dies, where will he/she be buried?”

“Limbo” means “an uncertain period of awaiting a decision or resolution, an intermediate state or condition.” Refugees live their lives in limbo. They don’t know what each day will bring, let alone where they will be when they die. Others will decide their destiny for them.

Refugees are people with many horrendous life experiences. They’ve suffered abuses at the hands of smugglers, in jungles, in employment. They have frequent nightmares and sleep very little. Many of them pray much and attribute much to God. They live lonely lives.

The way we think about God and what He expects of us can be fleshed out by the way we think about refugees.

As Christ-followers, as members of a minority community in Malaysia, how should we respond to refugees in Malaysia? What do theologians, immigration officers, police, RELA members, social workers advise?

What ‘special’ treatment, if any, can refugee members of a faith community (e.g., Christians, Muslims) reasonably expect from members of the same community in Malaysia?

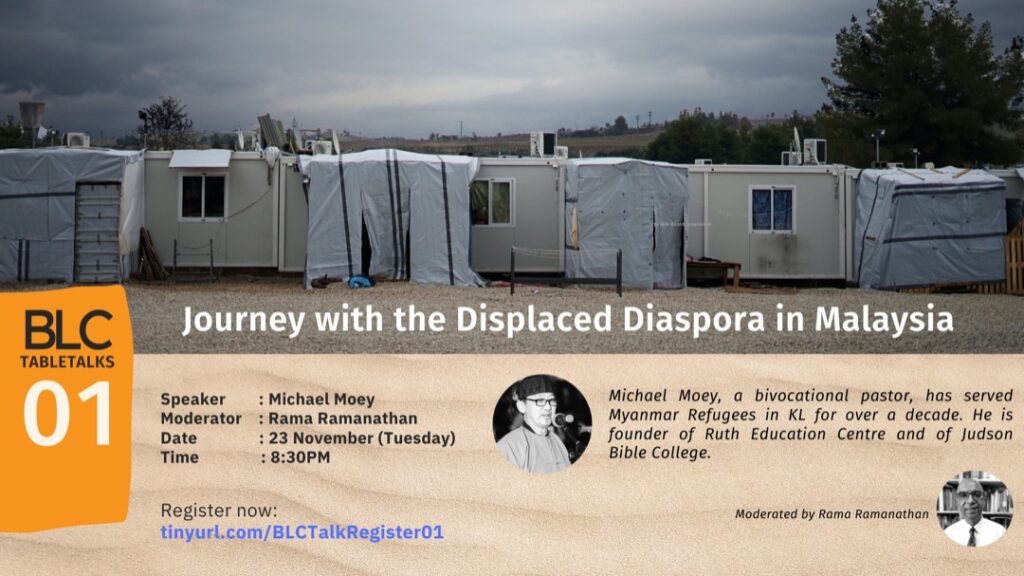

On Tuesday 23 November, 8:30 pm, Michael Moey, a bivocational pastor in Kuala Lumpur, will speak online about his engagement with refugees in Malaysia. You can join by registering at tinyurl.com/BLCTalkRegister01.

Note: This piece is loosely based on a Masters-level research paper about refugees in Malaysia written in December 2015 by a treasured friend.

To learn more about Rama, click here.