On the 21st of February, 1944, after 8 months in prison, Dr Alfons Wachsmann, in Brandenburg prison in Berlin, Germany, wrote a letter to his sister Minka. It’s first line is “At three o-clock I must die.”

Before his arrest and incarceration on 23rd June 1943, he had served for 15 years as parish priest and university chaplain in Greifswald. He was known for his activities in the mission for the conversion of Germany.

Father Wachsmann was “charged with doubting the accuracy of the figures quoted by the government to prove the success of the U-Boat campaign, with not placing implicit faith in the Fuehrer, and with not being confident of German victory.”

He was one of hundreds of priests who were hauled up after a letter issued by Pope Pius XI was read in Roman Catholic churches across Germany on 14 February 1943, the 5th Sunday of Lent, then known as Passion Sunday. Unusually, it was in German, not Latin.

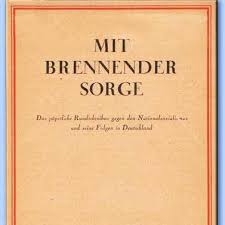

The encyclical, known as Mit Brennender Sorge, “With Burning Concern,” had been smuggled into Germany. Secretly, evading the Gestapo (state secret service), 300,000 copies had been printed in presses across the nation. Enraged, the Nazis shut down all those presses.

The encyclical was an official denunciation, by the church, of the policies of Hitler and his National Socialist (Nazi) party.

It was a confession in that it explained why the church had signed a concordat with Hitler four years earlier and was now breaking it.

It was also a confession in that it rejected the Nazi state’s policies of pantheism, racism, nationalism, and blind obedience to the Fuhrer (Hitler). It labelled these policies blasphemous, idolatrous, immoral, pagan, profane, provocative, reprehensible and much more.

It defended the Old Testament, which Nazi-oriented Christians wanted to excise from the Bible. It defended parts of the New Testament which the Nazis also wanted to excise.

It decreed that “The Church founded by the Redeemer is one, the same for all races and all nations” and called on Catholics “to square their faith and their conduct with the claims of the law of God and of the Church.”

It noted that “Secret and open measures of intimidation, the threat of economic and civic disabilities, bear on the loyalty of certain classes of Catholic functionaries, a pressure which violates every human right and dignity.”

While the Nazis invented a war-like, masculine Christ, it said “Humility in the spirit of the Gospel and prayer for the assistance of grace are perfectly compatible with self-confidence and heroism.”

It stressed, “To hand over the moral law to man’s subjective opinion, which changes with the times, instead of anchoring it in the holy will of the eternal God and His commandments, is to open wide every door to the forces of destruction.”

Against the background of the Nazis taking over youth clubs and schools, it declared “Laws and measures which … fail to respect this freedom of the parents go against natural law and are immoral.” (In a rally speech in 1936, Hitler had said that children “belong to their mothers as at the same moment they belong to me.”)

It objected to “the voluntary and systematic antagonism raised between national education and religious duty.”

Priests who read the letter must have been nourished by these words:

“The priest’s first loving gift to his neighbours is to serve truth and refute error in any of its forms. Failure on this score would be not only a betrayal of God and your vocation, but also an offense against the real welfare of your people and country. … to all those who in the exercise of their priestly function are called upon to suffer persecution; to all those imprisoned in jail and concentration camps, the Father of the Christian world sends his words of gratitude and commendation.”

The letters of Father Wachsmann reveal a man who was dedicated to his sister (“Minka”) and to his congregation. He prayed unceasingly for them.

He endured much hardship, from sleeplessness due to bedbugs to being in a locked cell while air raid alarms wailed, Allied bombs dropped nearby and the glass in the windows of his cell shattered – and were never replaced.

In 1943, a couple of days before Christmas, he wrote “Never before have I knelt before the manger as humbly as I shall this year. Everything has been taken from me — my home, my honour, my life. Thus I will kneel down before Him, Who had nowhere to rest His head, and Who died for the redemption of mankind. These gifts I bring: Hunger and cold, loneliness and desolation.”

From 1939 to 1943, hundreds of Catholic priests were arrested and tried for “oppositional activity”. Their names can be found in their church’s list of German martyrs of the 20th century, finalized in 1999.

Idolatry and injustice must be resisted. Retaliation is as certain as victory. Those who’ve gone before us teach us what it means to follow Christ and serve our neighbours.

Note: In a previous post on Pastor Niemoller, I touched on the Barmen Declaration of 1934, a Protestant response to Hitler.

Bibliography

Fest, J. C. (1979). The Face of the Third Reich. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin.

Hastings, P. (1952). Christ in Dachau. Oxford, England: Newman Bookshop.

Pius XI, P. (14 March, 1937). Mit Brennender Sorge. Encyclical. The Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

To learn more about Rama, click here.

The one in the picture is not Pius XI but Pius XII