“In our view, a Christian who is not charismatic – in the full sense of the word, that is to say, open to the Spirit and docile to his promptings – is a Christian forgetful of his baptism. On the other hand, a Christian who is not ‘socially committed’ is a truncated Christian who disregards the gospel’s commandments.”

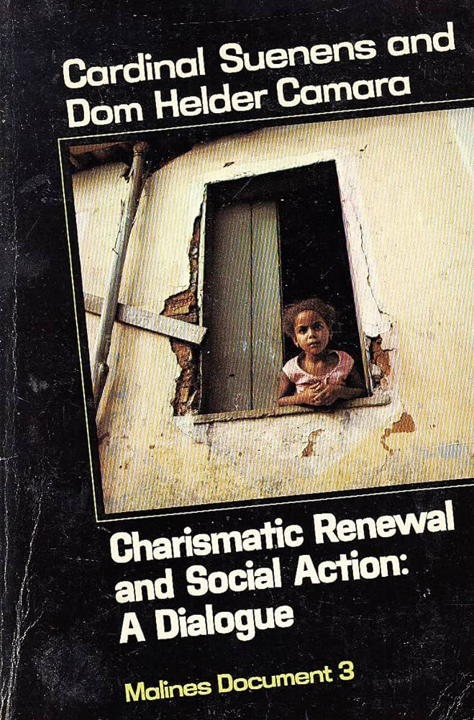

Those words were written in 1979. In a short book titled “Charismatic Renewal and Social Action: A Dialogue.”

The authors are two Catholic priests: Cardinal Leon-Joseph Suenens, Archbishop of Brussels-Malines (in Belgium), and Dom Helder Camara, Bishop of Olinda and Recife in Northeast Brazil, billed “the poorest and least developed part of the country.”

Camara is famous for having been treated as an internal enemy by the government of his own nation, Brazil, and for his aphorism:

“When I feed the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why they are poor, they call me a communist.”

Both men were key players in Vatican II, a formal church meeting or council, in Rome, of leaders of the Roman Catholic church, spread over four sessions, from October 1962 to December 1965.

The council changed many church practices. It gave a greater role to lay people; it viewed other churches and faiths more positively; it encouraged the replacement of Latin by local languages, and much more. It would not be far of the mark to say that Vatican II turned the church around.

Even literally! After Vatican II, when priests celebrate Mass, they don’t turn their backs to the congregation. Now, they face the congregation.

Suenens and Camara wrote in response to the charismatic renewal and liberation theology, both of which were prominent in the late 20th century.

In the charismatic renewal, Christians around the world received fresh energy and life-changing encounters with God. They received spiritual gifts, which the Bible calls “charisms;” they experienced healings; they spoke in languages called “tongues;” they sang and prayed for hours.

The term “Liberation theology” was coined to describe the thinking, about God, of Catholic priests who served the poor in Latin America. It describes a way of looking at Jesus and the Bible through the eyes of the poor. It’s practiced also in other nations, for example in Korea and India, where it’s called Minjun theology and Dalit theology.

Liberation theologians view the poor as victims of unjust, oppressive systems. And they view Christians as workers for justice and restoration.

Broadly speaking, Charismatics promoted a life focused on an other-worldly, vertical relationship with God. And liberationists promoted a life focused on a this-worldly, horizontal relationship with neighbours, both oppressed and oppressors.

In their book, Suenens and Camara show that all Christians are called to be both charismatic and liberationist.

Their book is very short, with an introduction and four chapters spread over 98 pages. The first three chapters are comprised of two parts. The first part is written by one of the authors. The second part is the other author’s response to the first part. Hence, the book is called a dialogue.

In the Introduction, Suenens urges that because God has spoken to us of “a coming kingdom,” we should be convinced that a more just society is not just an idle dream; and that if we are convinced, we should expect to labour with God to achieve it. This is what is meant by the verse Matthew 6:33 which reads “seek first the kingdom of God and his justice.”

The authors do not point it out, but most English translations render the last word in that verse “righteousness.” The word in Greek is dikaiosune. It can be translated as justice or as righteousness. In French, and in many languages spoken in Latin America, the word is translated “justice.”

In Chapter One, titled “Before God,” Camara proclaims that God’s intention, from the very beginning, has been for man to be His co-creator, “to tame nature and to complete his creation.”

Jesus wishes us to be “co-redemptors” with him, to liberate ourselves and all of creation from the effects of sin. To be effective, we must engage with God in prayer, for “Without prayer, there is no current, no Christian respiration.”

Camara reveals the stamp on his life of the doctrine of the incarnation of God in Christ by sharing a prayer he often prays, in words borrowed from the (English Catholic) Cardinal Newman:

“Lord Jesus, do not remain so hidden in me! Look through my eyes, listen through my ears, speak through my lips, act with my hands, walk with my feet … may my poor human presence recall, at least remotely, your divine presence.”

Suenens responds in dialogue. He amplifies Camara. He expounds the meaning of Paul’s words in Galatians 2:20, “It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me.” He writes:

“To live is to see, love, speak, and move. To live in Jesus Christ is to see with his eyes, love with his heart, speak with his lips, and follow in his footsteps.”

In Chapter Two, titled “At the Service of Man,” Suenens begins by declaring that “Every baptized person must accept responsibility for the social consequences of his Christian way of life.” He lists people who have made an impact on the world.

He includes the American Baptist Pastor, Martin Luther King Jr. together with Mother Teresa of Calcutta. He also quotes with approval a prayer composed by William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army.

Suenens speaks of evangelization and humanization, of sins of omission, of the work of the Holy Spirit. He briefly recounts the “problems which imperil” us. Then he says we must “enter the Upper Room, then come out into the public square and bear witness with a humble and brotherly assurance.”

He is, of course, referring to the energizing, by the Holy Spirit, of the 120 disciples on the day of Pentecost. He also urges us to be acutely aware that “the prince of darkness is not idle.” He says:

“Today’s idols are no longer called Baal or Astarte. They are called the profit-making and consumer society, or again, the permissive society, surrendering to the whims of the moment. And we worship them each time we acquiesce to inhuman dictatorships, to unjust wars, to racial discriminations, just ‘to avoid something worse.’ In bygone days Christians died because they refused to burn a few grains of incense to an idol. Usually, today’s Caesar no longer bears a proper name: he is called by the general mood of our time, by the search for ‘self-realization,’ for personal power, for material prosperity no matter the cost.”

Camara responds in dialogue. He adds that a Christian is “a new man,” who looks at the world with the eyes of faith, and therefore has a triple duty: he must “see, judge, and act.” On judging, this man who was called both saint and communist, doesn’t mince his words. He pleads:

“How dare we look at Christ if we who wear his name as our shield and call ourselves his disciples are contributing, for our part, to the scandal of this century: a small minority enjoying vast means of existence and enrichment while the great majority of God’s sons are reduced to a subhuman existence?”

Camara tells us that the poor dare not speak for fear of being crushed by the strong. But he stresses that their fear is unfounded, for “any community nourished by a living liturgy will have faith, hope and love.” It cannot be crushed by any human force, for God dwells with them and listens to their outcry.

Camara urges Christians to teach “the duty of speaking out, protesting, launching campaigns for the improvement of physical and moral health.” He gives a list of his “deepest social convictions.” His list includes this declaration: “We have no right to blame God for injustice and its attendant evils; it is for us to do away with injustice.”

In Chapter Three, titled “Apostles of Christ,” Suenens focuses on the Pentecost. He says:

“Pentecost evokes tongues of fire over the heads of the apostles: the symbol of the mission of Christians throughout the ages, the answer to Jesus’ prayer: “I have come to bring fire to the earth, and how I wish it were blazing already!” (Luke 12:49) To receive the Spirit and to witness to Jesus are one and the same thing: it is only to reveal him that the Spirit comes.”

Suenens recalls our Master’s command that we are to shout the good news of the gospel from the rooftops. He reminds us that doing so will be natural, if our faith is – as it should be – “the mainspring of our joy.” He expounds John 10:10 “I came that they may have life and have it abundantly;” he says we cannot keep this glorious, inexhaustible source to ourselves.

Suenens says the penetrative power of scripture is enhanced by the lives we lead. He reminds us of the communicative power of our attitudes, our incantations, our gestures, and our smiles. But he doesn’t diminish the role of the Spirit. He reminds us of what Paul wrote to the Thessalonians, which we read in chapter 1, verse 5: “… our gospel came to you not only in word, but also in power and in the Holy Spirit …”

Camara responds in dialogue. He addresses several notes to “Charismatics, my brothers.” In one of them, he says:

“No one has the monopoly of the Holy Spirit. Let us always remember that we have to receive his gift in all humility (we are not better or greater than anyone else), and that the charisms are of no account unless they are placed at the service of brotherly love. He who has no love and humility cannot advance on the Lord’s path, not even by one step. I invite you all to live under the action of the Spirit and, at the same time, to let yourselves be led by him to the very heart of the world, to the heart of men’s problems. You have to pray and to act at one and the same time.”

He supplies a list of four negatives and eight positives to be constantly in prayer about. These are things to avoid and things to do. Things to avoid includes using prayer as a pretext for neglecting social and evangelistic action. Things to do includes denouncing the idolatry of national security, and helping the Church overcome triumphalist temptations.

In Chapter 4 titled “In the Heart of the City,” Suenens discusses two conflicting tendencies among Christians. The first is conservatism which urges non-engagement with socio-political matters. The second is progressivism, which “regards human advancement … as an integral dimension of evangelization,” and holds that the church must challenge every form of established disorder. He warns that patterns of culture constitute a real indoctrination which soaks into us. He says:

“A society is not just the sum total of its members. It obeys specific laws due to the stability of its institutions, to a richness of a powerful continuity, but also to the passivity of a body of people, to a gregarious instinct and to a law of inertia.”

Suenens says it is impossible to improve conditions for people in the Third World without imposing “substantial taxes” on “consumer goods in proportion to their non-essential character.” He quotes with approval the words of the Protestant theologian Clark Pinnock, who wrote:

“If charismatic and evangelical Christians together were committed to the righteousness of the kingdom of God, as they ought to be, in the context of the societies where they have been called, they would represent a more radical force than any revolutionary group in existence. The dynamism is there. What is needed is wise pastoral direction and encouragement.”

Suenens argues that politics when done right, looks to the common good; therefore, politics involves the Church and its pastors, whom he calls “ministers of unity.” He says we have to break away from sinful structures which institutionalize evils such as selfishness, greed, injustice, oppression, and flagrant inequalities.

Suenens observes that when Mary welcomed the Spirit on the morning of the Annunciation, she made possible the Incarnation, the starting point of our salvation. This should induce us to open ourselves to the Spirit of God.

The book shows how two Christian leaders responded, theologically, to a conflict within the Christian community. A conflict between conservatives and progressives, charismatics and liberationists.

Their response is infused with God the Holy Trinity, God-in-community. Their response values the thinking and practice of non-Catholic Christians. Their response is evergreen, because it upholds the gospel without downplaying reality. Their response propels us “to go and do likewise.”

The great need of the church is docile Christians. Christians who know that they are daily drenched in the spirit of the world. And therefore, must daily, actively, seek to be strained, squeezed, and shaped by the Spirit. Both as individuals and as communities of faith.

Dare we commend, pray for, and seek after docility?

Peace be with you.

To learn more about Rama, click here.