Today’s column is not about the lectionary text for this Sunday. It’s about the Parable of the Talents, found in the Gospel according to Matthew in 25:14-28 and in the Gospel according to Luke in 19:12-27.

It’s a parable. I’ll tell it briefly. A rich man, before leaving on a long trip, gives money to each of three of his servants. Time passes. He returns. They report to him. Two of them invested the money and doubled it. The Master says to each of them: “Well done, good and faithful servant.” The third returned the money. All of it. He’d kept it safely. He said he didn’t do business with it because he feared he might lose some of it, be unable to return all of it, and have to face the wrath of his “hard” Master. Yet the Master punished him severely. Why? Because he didn’t, at the very least, put the money on deposit and earn interest on it.

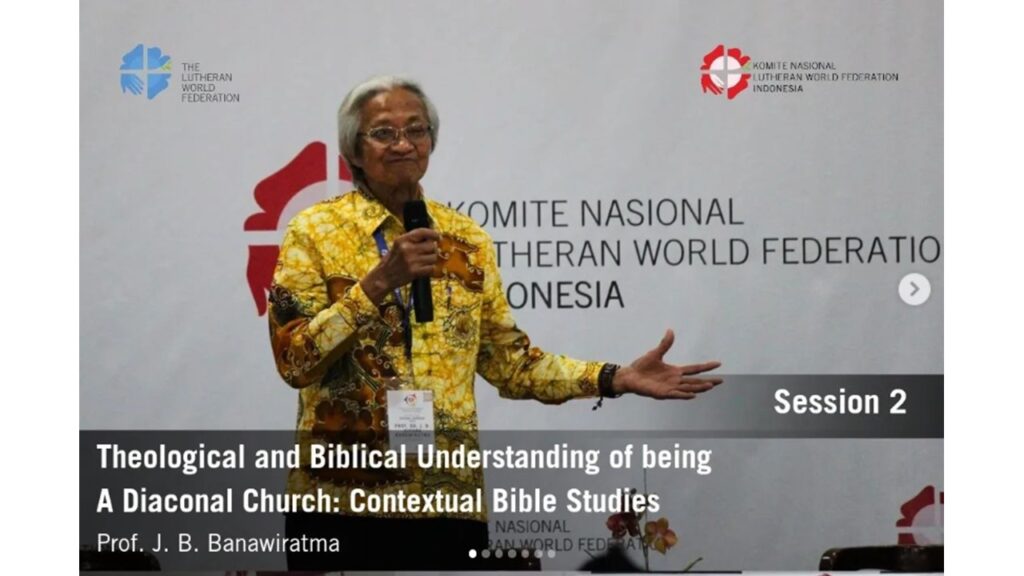

On Wednesday, I heard Professor Dr. J.B. Giyana Banawiratma (“Pak Bono”) give a talk titled “Theological and Biblical understanding of being a Diaconal Church – Contextual Bible Studies,” at the LWF Southeast Asia Diaconal Workshop 2023 in Parapat, Indonesia.

Pak Bono said he could not conceive of how the Jesus of the gospels, the merciful Jesus, could have approved of what the Master did to the third servant, the one who returned the money to him. I thought there was a grain of truth in what he said. I was deeply troubled. Pained.

For pain relief, as soon as I got home, I began researching. I found much commentary on the parable. There’s much about the differences in the two (or more) accounts of it, its placement in the flow of the gospel narratives, the apocalyptic sense in it, and much more. I’ll just focus on whether Jesus presented “the Master” positively or negatively.

Is the point of the parable to teach us how to gain the Master’s approval? Did Jesus commend the two servants who “invested well,” or did he commend the servant who was punished? Professor Richard L Rohrbach says:

The returning master admits to what the third slave knew ahead of time: that he is a “hard” (the Greek term here, skleros, is used by ancient writers to describe someone who is cruel, merciless, or arrogantly inhumane) man who “reaps where he did not sow and gathers where he did not scatter seed” (Matthew 25:24). The perfect definition of a thief! How have we missed that? Moreover, the master in Luke’s version is even worse. There he owns up to this same merciless attitude but then goes much further: ordering his enemies slaughtered in his own presence.

And what about the third slave, the one so bitterly rebuked by the returning master and vilified in virtually all Western interpretation for failing to invest the money? In Matthew, he buries the deposit for safekeeping. The rabbis argued that this was precisely the right thing to do so the deposit could be returned intact (b. Baba Mezi’a 42b; m. Baba Batra 4:8.) In fact, they ruled that burying the deposit meant the trustee was not liable if a loss occurred. Though the Lukan slave ties the money in a cloth—thus taking what the Mishnah specifies as the riskier course—he nonetheless preserves the pound as any honourable man would. He does not participate in the scheme to double the master’s money, but honourably refrains from taking anything that belongs to the share of another.

In both versions of the story, the third slave is told he should have invested the money with bankers so the master could have at least earned interest on his money. But seeking interest from another Israelite was forbidden by the Torah (Deuteronomy 23:19–20), and, elsewhere in Luke, Jesus says that we should lend “expecting nothing in return” (Luke 6:35). Even more telling is a third version of this parable quoted by Eusebius (265–339 C.E.) from the now-lost Gospel of the Nazoreans. There Eusebius is quite explicit that the hero of the story is the third slave who refused to cooperate in the investment schemes of the greedy master (Theophania 22).

Is the story a veiled commentary on [Herod] Archelaus, ethnarch of Samaria, Judea, and Idumea, the socio-political Master of the day? Pak Bono, drawing on Richard Horsley, said:

The parable says “a noble man went to a distant country to get royal power for himself and then return.” Behind this parable was a historical event. The noble man was Archelaus, son of Herod the Great. He summoned ten of his slaves, and gave them ten minas, and said to them, “Do business with these until I come back.” (v. 12-13). He did injustice business and wanted to exploit his slaves.

Jesus was not talking about developing mina or talents. His message was to resist exploitation and oppression. The hero was the slave who confronted the evil will of the king.

This interpretation is according to the context of the parable. Jesus was near Jerusalem (v. 11), approaching his crucifixion because he resisted all kinds of oppression by proclaiming the Kingdom of God.

Have we been missing the real hero of the story? I’m haunted by the feeling that Pak Bono may be right.

Peace be with you.

To learn more about Rama, click here.