Rothney Tshaka made me think hard about black liberation theology.

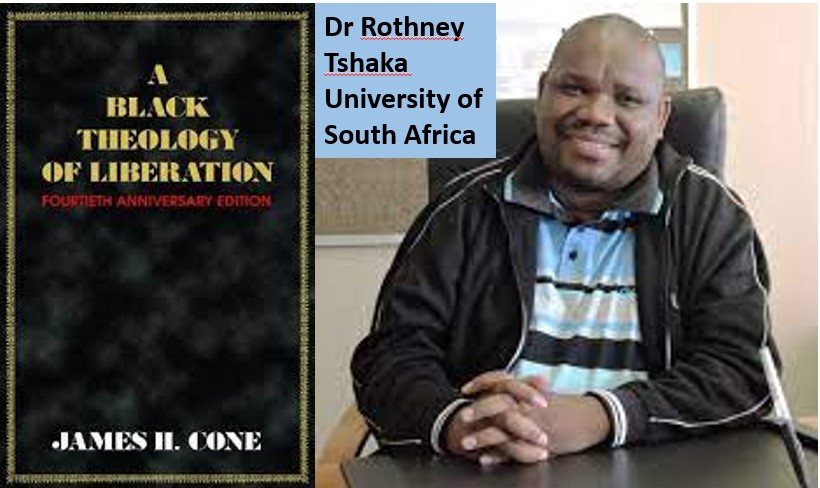

Tshaka’s the Director of the School of Humanities in the University of South Africa (Unisa). In his 19-minute contribution to the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) series on Public Theology, he introduces himself as an ordained minister, a student of black liberation theology, and author of a Ph.D. thesis on the influence of Karl Barth in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa.

Tshaka says black liberation theology is a means to an end, a process of getting to an objective. He says the objective is justice, the complete acceptance that all mankind is fully and equally human.

Tshaka says black liberation theology is a commitment to be particular and contextual, to be in conversation with, and to offer commentary about present, lived experiences, often of oppression.

It’s embarrassing. There is such a thing as oppressive theology. And it’s not just in Africa. It’s present even in developed, Western countries.

James H Cone, the theologian of the USA’s Black Power Movement, when he turned 60 in 1999, wrote a book called “Risks of Faith: The Emergence of a Black Theology of Liberation, 1968-1998.” He wrote:

Sunday was the most segregated day of the week … Although whites posted “Welcome” signs outside their churches, ostensibly beckoning all visitors to join them in worship, blacks knew that the invitation did not include them. “What kind of Christianity is it that preaches love and practices segregation?” my brother Cecil and I, budding young theologians, often asked each other. “How could whites exclude black people from their churches and still claim Jesus as their Savior and the Bible as their holy book?” (page xi)

Like Tshaka, Cone wrote a Ph.D. dissertation about an aspect of the theology of Karl Barth. He did it because he thought that effort would equip him to communicate the Christian faith to persons anywhere in the world: “Who would not feel adequately endowed after plowing through twelve volumes of Barth’s Church Dogmatics?” (page xiv).

But the civil rights movement of the 1960s, and the speeches of Martin Luther King Jr. and of Malcolm X, awoke him from his “theological slumber.” He concluded:

I knew deep down that I could not repeat to a struggling black community the doctrines of the faith as they had been reinterpreted by Barth, Bultmann, Niebuhr, and Tillich for European colonizers and white racists in the United States. I knew that before I could say anything worthwhile about God and the black situation of oppression in America, I had to discover a theological identity that was accountable to the life, history, and culture of African American people (page xiv).

After what he called his “black conversion,” (page xxii) he began writing. First, the essay “Christianity and Black Power (1967),” then the book “Black Theology and Black Power (1969).” He describes the Barth-like elation he felt after writing the book:

I suddenly understood what Karl Barth must have felt when he first rejected the liberal theology of his professors in Germany. It was a liberating experience to be free of my liberal and neo-orthodox professors, to be liberated from defining theology with abstract theological jargon that was unrelated to the life-and-death issues of black people. Although separated by nearly fifty years and dealing with completely different theological situations and issues, I felt a spiritual kinship with Barth, especially in his writing of The Epistle to the Romans (1921) and in his public debate with Adolf Harnack, his former teacher (page xxiii).

Tshaka alerts us to the tension between public theology and black liberation theology. He fears public theology may skirt around issues of colour and race, as was so often true in the past. He cautions that theology must be local before it is global. He warns that marginalization has always been the underside of globalization.

To learn more about Rama, click here.