This Sunday, the lectionary invites us to ponder Matthew 5:1-12. The English Standard Version supplies the heading “The Sermon on the Mount,” to verse 1, and the heading “The Beatitudes,” which means “supreme happiness,” to verses 2-12.

The Sermon on the Mount is Jesus’ best-known sermon. When I read it, I’m struck by the fact that Jesus began by evoking supreme happiness; and linked that “state of being” to a surprising set of eight statements.

The first four statements also describe states of being. First, sadness which is the state of being “poor in spirit;” second oppression, which is the state of having to be meek; third, mourning; fourth, injustice, which is the state of being “hungry and thirsty for righteousness.”

The next three statements are active. First, being merciful; second, upholding truth and justice, expressed as being “pure in heart;” third, making peace.

The final statement describes a state of being persecuted for upholding truth and justice.

Let’s put it bluntly: Jesus says it’s great to be poor, weeping and hurting!

Why did Jesus begin with blessings? And why did he label as “blessings,” things which we surely don’t want?

Let’s take a step back. Let’s look at what Matthew tells us just before he writes about the Sermon on the Mount. In 3:23-25 he tells us:

“[Jesus] went throughout all Galilee, teaching in their synagogues and proclaiming the gospel of the kingdom and healing every disease and every affliction among the people. So, his fame spread throughout all Syria, and they brought him all the sick, those afflicted with various diseases and pains, those oppressed by demons, epileptics, and paralytics, and he healed them. And great crowds followed him from Galilee and the Decapolis, and from Jerusalem and Judea, and from beyond the Jordan.”

So, Jesus was speaking to a huge crowd of people who had come to him, to be healed of severe diseases and crippling conditions. And he had healed them and freed them from demons. They were feeling blessed. They wanted more. They wanted to live in his shadow.

But Jesus wanted them to go home. He wanted them to be salt and light and peacemakers in their communities. He wanted them to adopt new perspectives, new ways of looking at things, and to change the societies in which they lived. He wanted them to change the world.

He wanted to show them that it was their poverty, sickness, and sadness, which had brought them to him, to get relief. He wanted to commission them to make things better.

Jesus didn’t lay out a set of laws. Didn’t lay out a beefed-up enforcement agency. No. He laid out a pattern of response built on an understanding of humans made in the image of God, rooted in a sense of right and wrong.

He began by showing them their desire to be in a state of joy: he repeatedly spoke of blessings. In the same sentences, he spoke of poverty, of suffering, of groaning under oppression.

Then he spoke of responses, of showing mercy, of making peace, of embracing truth and justice.

Then he spoke of tactics – very different tactics from the ones promoted by other social actors of the day.

Very different from the party of the Herodians and Sadducees, who formed alliances with the Romans. Very different from the party of the Pharisees, who turned to rigid adherence to the law, rejecting mercy. Very different from the party of the Zealots, who resorted to violence. Very different from the party of the Essenes, who became recluses.

As I meditate on the Beatitudes, three questions come to mind:

First, the question a lawyer asked Jesus: “Who is my neighbour?”

Second, the question Martin Luther asked: “How can a sinner like me experience the mercy of God?”

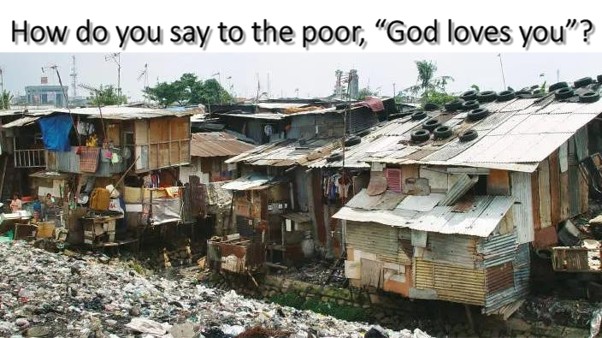

Third, the question the Peruvian priest, Gustavo Gutierrez, asked: “How do you say to the poor, ‘God loves you’?”

As I meditate, I think the last words in today’s passage sum up the wisdom Jesus imparted to those in the crowd who were listening:

“Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you.”

The gratitude of those who are healed will bear fruit as speech and actions. These will heal others. The healings will make oppressors feel insecure. They will respond with violence. But the healed will rejoice, because they know these are the birth pangs of a new, better society.

Are you healed? Are you bringing healing?

Peace be with you.

To learn more about Rama, click here.