This Sunday, the lectionary invites us to ponder Luke 19:1-10. The English Standard Version supplies the passage with the heading “Jesus and Zacchaeus.”

Jesus is in Jericho, surrounded by a crowd. Zaccheus learns that Jesus is approaching. He tries to spot Jesus. The crowd obstruct him. The crowd is hostile towards him because he’s a tax collector. He runs ahead and climbs a tree, to try to spot Jesus. Jesus comes to the tree. Tells him to come down. Tells him to take him home and show him hospitality.

Zaccheus is thrilled. The crowd grumbles. Because Jesus is going to sup with “a sinner.” Not just a tax collector. A chief tax collector. But Zaccheus tells Jesus he gives half his income to the poor. He says if anyone can prove that he’s been cheated by him, he’ll pay that person four times the amount he claims. Jesus believes him. Calls him a son of Abraham. Tells him, “today salvation has come to this house.”

Once, during a church Annual General Meeting, I referred to the contribution we paid to our denomination as a “tax.” The Council chairman and pastor quickly defended the contribution, saying it’s put to good use by headquarters, is spent on mission, social work, ecumenism, etc and so should be viewed positively.

They didn’t need to explain. Because I agreed with them. But they thought I didn’t. Because I used the word “tax.” For them, “tax” was not a neutral word. For them, “tax” was a negative word. Something undesirable. Something to be reduced or removed.

Such a view of tax was one reason the crowd around Jesus objected to tax collectors. There were other reasons: The taxes were often violently extracted, weren’t spent to reduce the suffering of the poor, and enabled the Roman government to make the lives of the people more miserable.[1]

Yet, despite all the bad things that could fairly be said about tax collectors, Jesus didn’t regard tax collection as a sin. Neither did John Baptist.[2] Neither did the leaders of the early church.

Why does Luke record the story of Jesus’ encounter with Zaccheus?

You may have heard preachers say that Zaccheus promised Jesus that he would give away half his wealth, and that he promised to compensate those whom he knew he had cheated.

But that’s not what the passage says. The passage doesn’t support our ideas about conversion, about salvation. It doesn’t speak of repentance. It speaks of a tax collector whose approach to life is the same as that of Jesus: we must care for the poor.

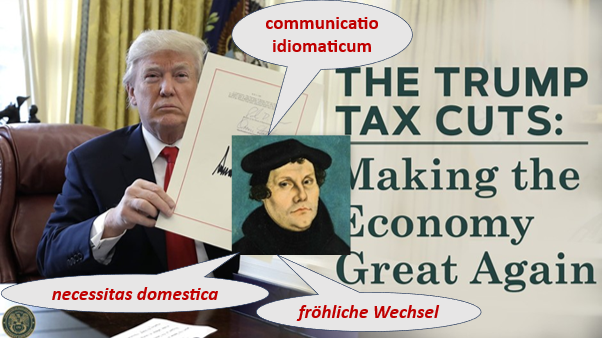

That brings me to Luther and what he did in the summer of 1522.

Five years had passed since he nailed his 95 theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, where he lived.[3] He was invited[4] to the city of Leisnig.[5] He was invited by the church there. He was invited to help them write a law. An ordinance which would establish progressive taxation, taxing the rich more than the poor; the basis for ensuring that everyone, rich or poor, could have a decent life; the basis for everyone having equal access to education; the basis for the welfare state – the reason why healthcare systems in Europe are overwhelmingly public, not private.

It’s also one of the reasons why in many countries in Europe, no collection plate is passed around during congregational worship, and they speak of “diaconal ministry.” This springs from Luther’s goal – crystallized in the Leisnig ordinance – to remove charitable work from the control of churches and place it in the hands of the state. Why? So that no priest could promise salvation to anyone who gave alms to the poor![6]

Over four centuries later, William Temple, an Anglican Archbishop in England, did something similar – he established the foundation of the welfare state in the United Kingdom.[7]

Once, in a year when there was a surplus in the national budget presented in Parliament, the Finance Minister[8] of the United Kingdom proposed a cut in taxes. Temple disagreed. He said the surplus should be given to the unemployed.

In 1941, Temple led a meeting of the leaders of the Anglican Church. It’s known as the Malvern Conference. The report of that conference became one of the foundations of the welfare state. An article in Time Magazine in November 1944 said,

“Reading Malvern’s recommendations, Britons realized that the Church of England was trumpeting nothing less than a social revolution, it could no longer be dubbed the Tory Party at Prayers.”

As we ponder the encounter between Zaccheus and Jesus, and observe Reformation Day, who can help us understand what in Malaysia is similar to Leisnig and Malvern? Do you agree with Luther and Temple? Should churches campaign for higher taxation and expanding public healthcare?

Peace be with you.

Additional note: There is an ongoing crisis in the Malaysian healthcare system. You can watch a discussion of it here: Is Malaysia’s Public Healthcare System Failing or Evolving? Are any Christian groups discussing it? Giving advice? Making proposals?

[1] As I said in my column last week, Mercy Over Merit: Lessons from the Pharisee and the Tax Collector.

[3] On 31 October, which we observe as Reformation Day – Friday this week.

[4] This invitation is very different from that issued from Medina in 622 AD. The people of Medina are said to have desired a governor. The people of Leisnig desired a consultant.

[5] Leisnig was a town near the birth village of Johann von Staupitz (145-1524), the Augustinian monk who supervised Luther.

[6] For a basic introduction to Luther’s thoughts and activities related to taxation and charitable work, read Martin Luther and Tax: A Protestant Perspective on Redistributive Taxation, by Rhys Laverty: Martin Luther and Tax: A Protestant Perspective on Redistributive Taxation – The Davenant Institute. Luther based the ordinance on eucharistic theology. Key terms are communicatio idiomaticum, fröhliche Wechsel (happy exchange), material redistribution.

[7] I spoke about this in my sermon titled Death and Taxes, BLC, 21 September 2025.

[8] More properly, The Chancellor of the Exchequer.

To learn more about Rama, click here.