If you were to transport a medieval peasant to a modern megachurch service, the language might be unfamiliar, but the underlying transaction would feel hauntingly familiar. The flashing lights and electric guitars would be bewildering, but the core message—”Give money to this religious institution to secure your divine favour”—would be a concept they understood all too well. It was called the sale of indulgences, and it was the spark that ignited the Protestant Reformation.

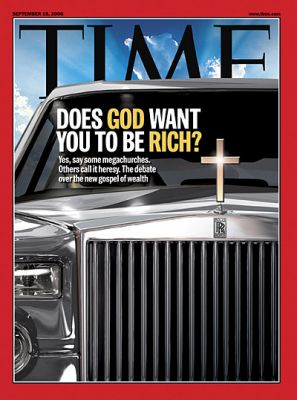

Five centuries later, a profound irony has come full circle within the very movement that broke from Rome: the Prosperity Gospel is a rebranded version of the medieval indulgence, and its influence is keenly felt in Malaysian churches today.

Editor’s note: This article is published to commemorate Reformation Day which falls on Friday, October 31, 2025. Reformation Day is an annual commemoration of the events of the Protestant Reformation, which began in 1517 with Martin Luther’s posting of the 95 Theses.

The Transactional Gospel: Give to Get

At the heart of both systems lies a simple, powerful, and deeply appealing proposition: your financial contribution is a direct investment in divine blessings.

In the late medieval period, the Roman Catholic Church had developed a complex doctrine around Purgatory—a place of temporary punishment where souls were purified before entering Heaven. An indulgence was a way to reduce this time of suffering, either for oneself or for a deceased loved one. While initially tied to acts of penance, by the time of Martin Luther, the practice had become heavily commercialized. Papal fundraisers like Johann Tetzel travelled from town to town, famously chanting the jingle: “As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs.” The transaction was explicit: your money purchases spiritual relief and a guarantee of salvation.

The Prosperity Gospel operates on the same psychological principle, albeit its promised rewards are often more earthly and immediate. In Malaysia, this often manifests in teachings around “seed of faith” and “sowing for a harvest.” Congregants are encouraged to give sacrificially, especially during rallies and conferences or special fundraising drives for a new “vision” (like a church building or media studio), with the promise that God will multiply their offering. The desired “harvest” is often framed in culturally specific terms: a visa to migrate to a desired country, success in the SPM or university exams, healing from a chronic illness, or a promotion to lift a family out of B40 status. Verses like Malachi 3:10 are wielded as contractual agreements, promising that if you “bring the whole tithe,” God will “throw open the floodgates of heaven” with material blessings.

Whether it’s a coin for a soul or a “seed” for a visa or promotion, the core message is identical: You are told to give in order to secure a specific, desired blessing. Divine favour becomes a product, and the church is the checkout counter.

The Blame-Shifting Paradox: When the “Miracle” Doesn’t Materialize

This is where the system reveals its most insidious design. In both cases, the promised outcome fails to materialize for the vast majority of participants.

The medieval believer who bought an indulgence for a departed parent had no way of verifying its efficacy. Did their loved one’s soul actually ascend from Purgatory? They had to take the Church’s word for it. If a person remained spiritually troubled or their faith felt hollow, the doctrine provided a ready explanation: the problem was not with the indulgence itself, but with the individual’s own inherent sinfulness or lack of piety.

The Prosperity Gospel employs the same cruel blame-shifting strategy. When the promised breakthrough doesn’t materialize, the fault is never with the doctrine but with the giver—attributed to a lack of faith, an impure motive, or unconfessed sin.

This creates a cruel double bind, particularly potent in a culture that values “face” and spiritual attainment. Not only do followers lose their money, but they are also burdened with the spiritual guilt and shame for the doctrine’s failure. They are left poorer, both financially and emotionally, convinced of their own inadequacy.

Meanwhile, a small number of people benefit spectacularly. In the 16th century, the funds from indulgences built St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, enriching the papacy and its agents. Today, the “seed faith” offerings fund the lavish lifestyles of prominent church leaders. While not all Malaysian pastors embrace this, the model exists: the leader who flaunts their wealth as a “testimony” – the new car, the expensive watch, the overseas holidays – all justified as “blessings” from God and evidence that the system “works.”

This very contradiction was famously captured in a medieval anecdote about the theologian Thomas Aquinas. Upon being shown the vast papal treasury, Pope Innocent IV is said to have remarked, “You see, Thomas, the Church can no longer say, ‘Silver and gold have I none.'” To which Aquinas shrewdly replied, “That is true, Holy Father, but neither can she now say, ‘In the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, rise up and walk.'” This exchange cuts to the heart of the issue: the accumulation of temporal wealth often coincides with a diminishment of authentic spiritual power. The leaders become the living, breathing “proof” that incentivizes the masses to keep giving, but the money doesn’t flow upward to God; it flows horizontally, from the pockets of the hopeful congregation into the bank accounts of the anointed few.

The Ironic Full Circle.

This is the staggering irony that deserves a moment of silent reflection. The Protestant Reformation was built on a rejection of this exact spiritual economy.

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses were not a vague complaint about the Church; they were a direct assault on the theology and practice of indulgences. He argued that salvation was by God’s grace alone, received through faith, and not something that could be bought or sold. This was the theological bedrock of Protestantism: a personal, unmerited relationship with God, free from the transactional mediation of a religious institution.

Fast forward 500 years, and we see a dominant strand of Protestantism in Malaysia and elsewhere having come full circle. The preachers who proudly stand in the Protestant tradition now preach a doctrine that Luther would have decried as a “theology of glory”—one that emphasizes earthly reward and tangible payment for piety. They have rebuilt the very “supermarket of salvation” that their spiritual ancestors tore down.

The language has changed from Latin to the various languages used in Malaysia. The currency has shifted from coins to Touch ‘n Go, bank transfers, and QR code payments. The promise has shifted from post-mortem relief to pre-mortem wealth and success. But the core mechanism—pay for grace—remains unchanged.

What Does the Bible Actually Teach?

The Prosperity Gospel selectively uses Scripture, often stripping verses from their context. The broader biblical narrative presents a very different picture of wealth, suffering, and generosity.

A warning on the Sin of False Generosity.

The Story of Ananias and Sapphira (Acts 5:1-11)

This narrative provides a crucial counterpoint to Prosperity theology. A couple sold a piece of property and publicly presented the entire proceeds as their gift to the church, while secretly holding back a portion for themselves. Their sin was not in keeping some of the money—Peter explicitly says, “Didn’t it belong to you before it was sold? And after it was sold, wasn’t the money at your disposal?” (Acts 5:4). Their sin was deception—lying to the Holy Spirit to gain a reputation for extreme generosity they did not deserve. Similarly, the Prosperity Gospel often creates pressure to appear more generous than one can be, in order to “unlock” a blessing. In Acts, judgment came for leveraging faith for social prestige; today, followers are often shamed for not leveraging their finances enough for personal gain.

Warnings Against the Love of Money

Matthew 6:19-21:

“Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth… But store up for yourselves treasures in heaven…”

1 Timothy 6:9-10:

“Those who want to get rich fall into temptation and a trap and into many foolish and harmful desires that plunge people into ruin and destruction. For the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil…”

Note: 1 Timothy does NOT teach that money per se is evil. It is the LOVE of money that is the problem.

Salvation and Generosity are by Grace, Not Transactions

Ephesians 2:8-9:

“For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast.”

Romans 3:24:

“…and all are justified freely by his grace through the redemption that came by Christ Jesus.”

2 Corinthians 8:9:

“‘For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor, so that you through his poverty might become rich.”

This reframes giving not as a payment for wealth, but as a response to Christ’s poverty.

Luke 6:32-36:

“If you love those who love you, what credit is that to you? Even sinners love those who love them. And if you do good to those who are good to you, what credit is that to you? Even sinners do that… But love your enemies, do good to them, and lend to them without expecting to get anything back. Then your reward will be great, and you will be children of the Most High, because he is kind to the ungrateful and wicked. Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful.”

In this passage, Jesus dismantles the idea of a quid-pro-quo faith. The call to lend “without expecting to get anything back” is a direct rebuke to the “give-to-get” calculus. The reward is not a material return, but the profound spiritual reality of resembling a gracious and merciful God.

2 Corinthians 9:7:

“Each of you should give what you have decided in your heart to give, not reluctantly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver.”

This emphasizes a free, cheerful decision—a stark contrast to the pressured ‘sowing’ driven by the fear of missing a blessing.

Conclusion

The enduring appeal of both indulgences and the Prosperity Gospel lies in their offer of certainty and control in an uncertain world, a temptation as real in Klang Valley as it was in Wittenberg. They reduce the mysterious, often difficult journey of faith to a simple transaction. But this commodification of divine favour is not only theologically bankrupt; it is spiritually predatory. It preys on hope and fear, leaving a trail of financial and spiritual wreckage in its wake.

The lesson of history is clear: whenever faith becomes a financial transaction, the only miracle that consistently occurs is the transfer of wealth from the poor and desperate to the powerful and wealthy. The Reformation was fought to break this cycle. The reincarnation of the practice of indulgences in the form of the Prosperity Gospel is one of the great tragedies of modern religious history.

Ultimately, the biblical path grounds us in a profound truth expressed in the prayer of King David: “Yours, Lord, is the greatness, the power, the glory, the splendour, and the majesty; for everything in heaven and on earth is yours. All things come from you, and of your own do we give you.” (1 Chronicles 29:11, 14). Our giving is not a purchase of favour but a grateful return of a portion of what God already owns. It is from this posture of worship and acknowledgment that a truly Christ-like generosity flows—a generosity that finds its ultimate motive not in a contract for personal gain, but in a simple, transformative command from Jesus himself: “Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” (Matthew 25:40)

This truth shatters the transactional paradigm. We do not pay God for blessings; we give to Christ out of gratitude, recognizing we are merely returning what was already His. Let us, therefore, reject the Prosperity Gospel in all its forms. In doing so, we honour Christ by upholding the very Reformation heritage that fought to liberate faith from such bondage.

References For Further Reading & Fact-Checking:

- Luther, Martin. Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences (The 95 Theses). 1517. English version accessible at https://fellowshippres.org/wp-content/uploads/My-PDF-95-Theses-Martin-Luther-9-25-2017.pdf

- Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400-1580. Yale University Press, 1992.

- On the modern Catholic doctrine on indulgences, see https://www.vatican.va/content/catechism/en/part_two/section_two/chapter_two/article_4/x_indulgences.html

- https://theconversation.com/the-catholic-view-on-indulgences-and-how-they-work-today-193066#:~:text=In%201517%2C%20the%20German%20theologian,Cabrini%20in%20Chicago%20offered%20indulgences.

- Bowler, Kate. Blessed: A History of the American Prosperity Gospel. Oxford University Press, 2013.

- The Bible For Normal People – Episode 181: Kate Bowler – The Prosperity Gospel & a Theology of Suffering. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2EUjqJHm9yU

- The preachers getting rich from poor Americans. https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-47675301

- Paying for prayer: I went into debt, trying to secure a miracle. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-64881435

- Hanegraaff, Hank. Christianity in Crisis. Harvest House Publishers, 1993.

Read more about Davin here!