Tomorrow, 10th of October, is the 19th World Day Against the Death Penalty. It’s “a day to advocate for the abolition of the death penalty and to raise awareness of the conditions and the circumstances which affect prisoners with death sentences.”

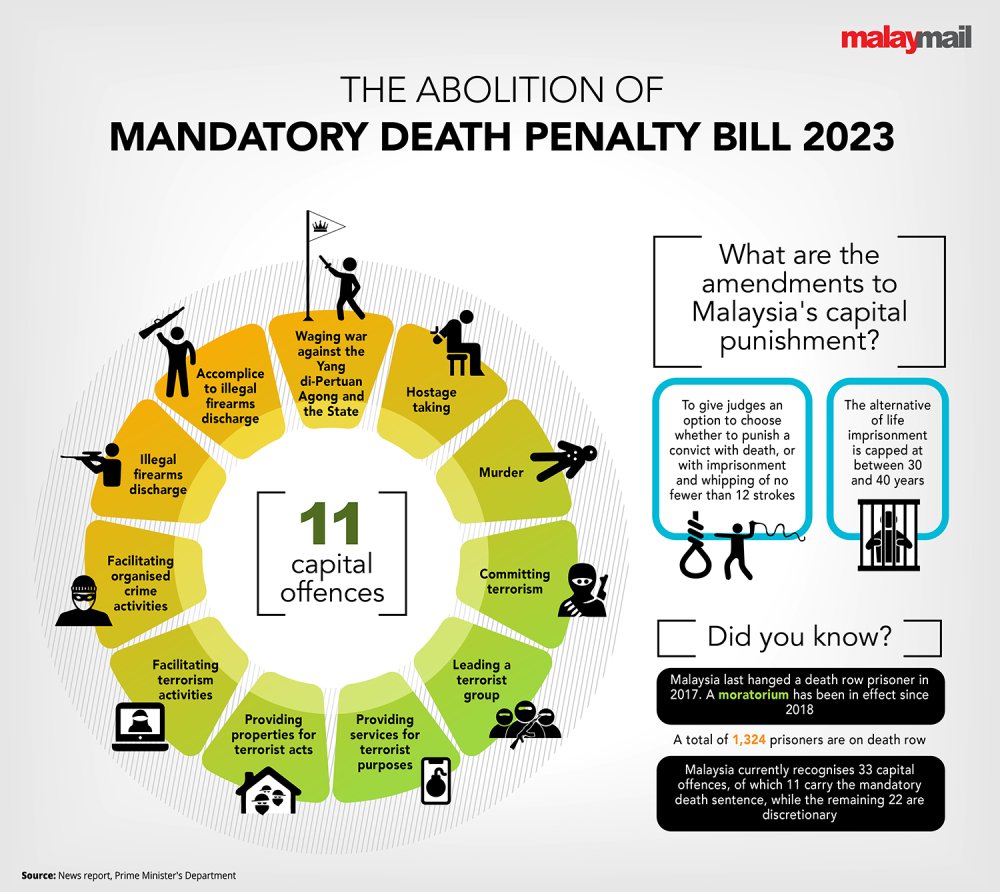

In Malaysia, until the 3rd of July this year, the death penalty was mandatory for 11 offences. On the 4th of July, the Abolition of Mandatory Death Penalty Act 2023, came into operation. The death penalty is no longer mandatory – but it has not been abolished. As far as I know, Malaysian churches did not participate in the campaigns behind the bill and did not mark 4 July 2023 with messages or thanksgiving services.

We live in an era when pastors are thought of as officiants at services, baptisms, communions, deaths, and weddings; counsellors; companions. Few are aware that ethics and justice, and therefore public policy, is taught in seminaries – which our pastors are required to graduate from before they are ordained – and presumably speak about and advocate for.

Some members of our congregation have wrestled with such questions and have written essays in response. This week, we share with you one such essay. Beyond discussing the death penalty, this essay demonstrates how seminarians extract the biblical teaching from the text – and present it in a relevant way. Enjoy!

Should Christians in Malaysia support the death penalty?

The death penalty is often in the news. As is often the case, Christians are largely divided into those for the death penalty and those against it. Emotions run high, with no shortage of claims to Biblical support from all sides.

While supporters of capital punishment tend to argue that two completely different norms apply to church and state, I agree with Christopher Marshall. He wrote in Beyond Retribution that if we conclude that capital punishment is consistent with a Biblical-Christian ethic (on grounds of theology and morality), then Christians must be prepared to participate in the enforcement of capital punishment as judges, prison officers, and executioners.

Conversely, if we decide that capital punishment is contrary to such an ethic, then Christians should work towards its abolition in countries that still employ it and oppose all attempts to reintroduce it in countries that have dispensed with it.

Of the range of punishments currently employed in modern penal codes, the death penalty is unique because it could claim Biblical sanction, if desired. However, we must consider several factors at length if we wish to arrive at an authentically Christian position on capital punishment.

Here are some important questions to ask:

- Do the New Testament’s teachings supersede the Old Testament’s teachings on this issue, or do we go by the teachings in the Old Testament?

- We also ask the theological and philosophical question of how we are to understand the nature and function of justice. Should justice be conceptualised in retributive terms, where “punishment fits the crime”, or In restorative terms — does capital punishment restore the well-being of society and promote healing in the lives and relationship of those involved?

- On the pragmatic side, we must ask if capital punishment is beneficial or harmful to society.

If you haven’t already noticed, death penalty and capital punishment refer to the same thing. We will be using both terms interchangeably.

Beginning with the Old Testament

We begin right at the beginning of the Bible. Discussions of the death penalty typically involves Genesis 1:27:

So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.

The purpose of this is to invoke the idea of the sanctity of life. You could say that this is the Biblical and theological foundation to the argument for and against murder and capital punishment. The question then is — what does being “created in the image of God” mean?

Being “created in the image of God”

There are several points to note about this much-used Bible verse.

First, we must understand God and understand man.

Wayne Grudem wrote in Systematic Theology that “a full understanding of human likeness to God would require a full understanding of who God is, God’s being and actions, and a full understanding of who humans are and what we do.”

It is like if we know a mother and we know her daughter respectively. As we spend time with both of them, we might recognise the similarities between the two. Perhaps they both enjoy spicy food, or they both have a love for the outdoors.

In the same way, the more we know about God, the more we would be able to spot the similarities between God and humans, and all the ways humans are like God.

Second, there are three main views about what it means to be in the “image of God”.

In his book Christian Theology, Millard J. Erickson listed three views on the nature of the image.

- The substantive view — there are certain characteristics within the human nature, may it be physical, psychological, or spiritual.

- The relational view — the image is not intrinsically present in humans but is experienced as a relationship between humans and God.

- The functional view — the image is not something the human is, but rather something the human does.

Third, it is hard to reconcile the three views with the way the word “image” is used in the Bible. But there are some things we do know:

- The image of God is universal within the human race.

- Thus, we are to relate to each other with the respect due to fellow bearers of God’s image. We must neither deprive someone of their freedom nor encroach upon each other’s legitimate exercise of dominion.

- The prohibitions of murder (Genesis 9:6) and cursing (James 3:9-10) apply to both sinful humans as well as godly believers. From this, we infer that the image of God is not lost as a result of sin or the fall. From this, we conclude that the image of God refers to something a person is, as opposed to something the person does.

- To be human is to be capable of interacting with other people, thinking, and reflecting, and of having free will. It is these qualities of God that human beings have that makes worship, personal interaction, and work possible.

- As bearers of God’s image, humans belongs to God (Mark 12:13-17). We are fully human when we relate to God, relate to fellow humans, and exercise dominion over God’s created order the way Jesus did. Jesus is the complete revelation of the image of God.

- Furthermore, the divine image is also a shared, corporate reality that is fully present only in community. This assertion is consistent with the doctrine of the Trinity and finds implicit and explicit support in the creation narratives of Genesis 1:26-28 and Genesis 2:18-23.

Now that we’ve established the Biblical and theological foundations of the concept of being created in the image of God, let us evaluate the implications of this teaching in relation to murder and capital punishment.

Capital punishment in the Bible

Let us consider the following texts used to support capital punishment.

- Genesis 9

- Provisions in the Pentateuchal Law

- John 8

- Romans 13

The institution of the death penalty in Genesis 9:4-6

But you must not eat meat that has its lifeblood still in it. And for your lifeblood I will surely demand an accounting. I will demand an accounting from every animal. And from each human being, too, I will demand an accounting for the life of another human being. Whoever sheds human blood, by humans shall their blood be shed; for in the image of God has God made mankind.

Genesis 9:4-6 is often used by supporters of capital punishment as a clear authorisation for taking a human life as an act of retributive justice. According to Charles Daryl in his paper Outrageous Atrocity or Moral Imperative? to deny that the ultimate human crime should be met with ultimate punishment “is a moral travesty that fails to comprehend the imago dei (image of God) and blatant contradiction of universally repealed canons of moral truth”.

On the other hand, opponents of the death penalty interpret Genesis 9:4-6 as proverbial in that it is predictive and not prescriptive.

I remain unconvinced by the proverbial interpretation of Genesis as it ignores the divine endorsement that humans are made in God’s image (Genesis 9:6).

Provisions in the Pentateuchal Law and witness of the Old Testament

Christopher Wright wrote in Old Testament Ethics for the People of God about the provisions of capital punishment in the Pentateuchal Law from which the lex talionis (an eye for an eye) principle is derived.

He wrote, “The offender was to suffer his just deserts, which should be appropriate to the offence. That is the significance and justification of the lex talionis principle,” in regard to retribution.

He added that this did not mean unlimited vengeance, as it is often assumed to mean. Instead, the principle was “a simple, and almost certainly metaphorical, way of decreeing proportionality in punishment. It is to be understood as a law of limitation, preventing excessive or vengeful punishments. It was a handy way of saying the punishment must fit the crime.”

Wright goes on to say that the gradation of penalties in Israel’s laws are to be understood as a scale of values that gives priority to human life and relationships over property, possessions, and power. They are not a rigid set of punishments.

In The Death Penalty by James J Megivern, the author wrote that the law had a pedagogical function. That is, its purpose is primarily to educate. There was little evidence that Israel was a society that understood its law codes as mirrors of practice.

Consequently, opponents of capital punishment cite narrrative episodes in the Old Testament such as Cain’s murder of Abel (Genesis 4:8-16), Moses’ killing of the Egyptian (Exodus 2:11-14) and David’s murder of Uriah (2 Samuel 11:14-17) where God did not invoke the rule of Genesis 9:4-6. It should however be noted that in the case of David, punitive consequences were visited upon his own household (2 Sam 12:10-12). They believe this to be a demonstration of the importance to balance the prescriptions of Bible law with the pragmatic realities of the Biblical narratives.

In response, supporters of capital punishment say that exceptions to the general rule do not nullify the rule; they only limit its applicability.

Thus far, our survey of the Old Testament confirms the divine legitimation of the death penalty for murder.

But do the teachings in the New Testament repeal the death penalty of the Old Testament? We will address this in part 2 of our discussion.

Part 2

In the first part, we covered the main Old Testament passages dealing with the death penalty. In this second part, we will look at the New Testament passages and decide if the New Testament teachings revoke the death penalty of the Old Testament.

We begin with John 7:53 – 8:11

But Jesus went to the Mount of Olives. At dawn he appeared again in the temple courts, where all the people gathered around him, and he sat down to teach them. The teachers of the law and the Pharisees brought in a woman caught in adultery. They made her stand before the group and said to Jesus, “Teacher, this woman was caught in the act of adultery. In the Law Moses commanded us to stone such women. Now what do you say?” They were using this question as a trap, in order to have a basis for accusing him.

But Jesus bent down and started to write on the ground with his finger. When they kept on questioning him, he straightened up and said to them, “Let any one of you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.” Again he stooped down and wrote on the ground.

At this, those who heard began to go away one at a time, the older ones first, until only Jesus was left, with the woman still standing there. Jesus straightened up and asked her, “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?”

“No one, sir,” she said.

“Then neither do I condemn you,” Jesus declared. “Go now and leave your life of sin.”

Immediately relevant to the question of abrogation of the Old Testament by the New Testament is the story of the woman accused of adultery in John.

Having considered interpretation of key areas of the text by supporters and opponents of capital punishment, I echo Morris’s conclusion that when Jesus said “without sin”, he referred to the general sinfulness of the accusers and not just the sin of adultery.

Furthermore, Jesus did not explicitly abrogate the Old Testament requirements. The text says nothing about forgiveness from Jesus and repentance of the prostitute. Of course, we cannot say with certainty if the woman was indeed guilty of committing adultery.

Most importantly, when the crowd tried to execute the woman, Jesus challenged the right of the self-proclaimed “righteous people” to kill in the name of the rule of law.

Romans 13:1-7

Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God.Consequently, whoever rebels against the authority is rebelling against what God has instituted, and those who do so will bring judgement on themselves. For rulers hold no terror for those who do right, but for those who do wrong. Do you want to be free from fear of the one in authority? Then do what is right and you will be commended. For the one in authority is God’s servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for rulers do not bear the sword for no reason. They are God’s servants, agents of wrath to bring punishment on the wrongdoer. Therefore, it is necessary to submit to the authorities, not only because of possible punishment but also as a matter of conscience.

This is also why you pay taxes, for the authorities are God’s servants, who give their full time to governing. Give to everyone what you owe them: If you owe taxes, pay taxes; if revenue, then revenue; if respect, then respect; if honour, then honour.

Finally, we consider if Romans 13:1-7 should be understood as:

1) Conferring divine authority on the state to take human life, and

2) Whether “power of the sword” refers specifically to capital punishment.

Schreiner wrote that “the sword” refers to the broader judicial function of the state and not just capital punishment. He went on to say that Paul would not have flinched in endorsing the right of the ruling authorities to practice capital punishment for murder since Genesis 9:6 supports it.

This is however an argument from silence. There is no explicit reference to Paul endorsing capital punishment in Romans on the basis of Genesis 9:6.

Crucially, according to Bird, Romans 13:1-7 is summed up in verse 7 in Paul’s exhortation to his readers that they are obligated by law and by conscience to give rulers what they are owed — taxes, revenue, respect, and honour.

Bird acknowledges that Paul is definitely aware that the divinely appointed authorities do not always govern justly or treat people right. Thus, it is plausible that Paul’s advice in this passage is motivated more by the need to encourage the survival of the Christians in Romans who are a marginalised group, than by the enforcement of Biblical principles to support capital punishment.

Mark 12:13-17

Later they sent some of the Pharisees and Herodians to Jesus to catch him in his words. They came to him and said, “Teacher, we know that you are a man of integrity. You aren’t swayed by others, because you pay no attention to who they are; but you teach the way of God in accordance with the truth. Is it right to pay the imperial tax to Caesar or not?Should we pay or shouldn’t we?”

But Jesus knew their hypocrisy. “Why are you trying to trap me?” he asked. “Bring me a denarius and let me look at it.” They brought the coin, and he asked them, “Whose image is this? And whose inscription?”

“Caesar’s,” they replied.

Then Jesus said to them, “Give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s.”

And they were amazed at him.

Closely related to Romans 13:1-7 is Mark 12:13-17. There, Jesus reminds us that though humans are obligated by law to give rulers what they are owed, as the bearer of God’s image, humanity belongs to God. Noting the link between Mark 12:13-17 and Genesis 1:27, we are obligated to give to God what is owed to God. Importantly, because Jesus is the complete revelation of the image of God, and the church is called, as a community to imitate Christ, we are fully human when we relate to God and his creation the way Christ did.

The question then becomes, what does it mean to give God what is owed to God in the Malaysian context? To answer that, we must ask: Is the way the Malaysian government enforces capital punishment for murder compatible with the teachings of the Bible on capital punishment?

Malaysia Law and the Bible on Capital Punishment (prior to 4 July 2023)

Is the Malaysian law on capital punishment compatible with Biblical teaching? According to the Malaysian Penal Code, the death penalty is mandatory for the following:

- Murder

- Attempted murder for life-term prisoners

- Fatal terrorist acts

- Offences against the lives of the country’s political leaders

The Penal Code also authorises the death penalty as a possible punishment for

- Waging war against the state

- Kidnapping or abduction with the intent to murder

- Gang-robbery with murder.

In the case of drug trafficking, the mandatory death penalty is authorised by the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1952.

Thus, while the Malaysian Penal Code has points of compatibility with Biblical principles on capital punishment when it comes to murder, it also goes beyond what the Bible teaches in cases of attempted murder, and scenarios where murder did not happen. On the basis of lex talionis, we should be cautious in advocating support for capital punishment for cases where murder did not happen.

Also, in the above survey of Biblical passages common to capital punishment debates, I have shown that attempts to prove that Old Testaments provisions for capital punishment carry forward to the New Testament are at best arguments from silence.

In light of such a degree of uncertainty, dare we push forward in support of a punishment that does not allow us the possibility of error? Unlike other modern-day punishments, this is one punishment we cannot undo in the case of judicial mistakes!

It should also be noted that support for capital punishment is usually motivated by desire for retribution. In Western democracies, there is a rise in support for the reintroduction or increased use of death penalty at times of social upheaval, rising crime rates, or in the aftermath of particularly brutal crimes.

Perhaps, it is helpful to ask: is God more interested in the restoration of God’s image in the bearers, or retribution against those who destroyed it?

These are the two questions we will look at, together with extra-biblical considerations, in the part 3.

Part 3

In parts 1 and 2, we covered the main Old Testament and New Testament passages dealing with the death penalty. We ended our review of the New Testament passages, appropriately, with Mark 12 linking back to Genesis 1 on the significance of the image of God. Additionally, we noted that while the Malaysian Penal Code has points of compatibility with Biblical principles on capital punishment when it comes to murder, it also goes beyond what the Bible teaches in cases of attempted murder, and scenarios where murder did not happen. Finally, we ended part 2 with the question: Is God more interested in the restoration of God’s image in the bearers, or retribution against those who destroyed it?

Put differently, as Dr Robert Cochran asked in this Regent College Podcast, does our justice system punish with tears or does it punish with cheers?

Retributive Justice or Restorative Justice

We begin with the instance when God used capital punishment on Ananais and Sapphira who desired the praise of man over honour to God (Acts 5:1-10). The couple had sold their property, but then lied about the profits from the transaction. This angered God and God struck both of them dead. Notice how the couple did not murder anyone. How is Genesis 9 applicable here? What is happening?

It gets better, when we reach Acts 9, God decides to extend clemency towards a murderer, Paul, who approved of Stephen’s stoning (Acts 9:1-18). As we had noted in part 1 (insert hyperlink), this is not the first time God had offered mercy to a murderer.

Several things may be said, Darrell Bock, author of Acts, views the example of Saul in Acts 9 as the ultimate example of God’s initiative to save the enemy, who, more importantly, was still a sinner loved by God and in need of salvation. God rescuing Saul even replaces some of what was seemingly lost with Stephen’s death.

Again, we find consistency in the witness of Acts with the New Testament teaching that Christians are to overcome evil with good (Romans 12:17-21, 1 Peter 3:8-12). This observation compliments the Old Testament and New Testament teaching that vengeance is reserved for God who will right all wrongs at the eschaton(Deuteronomy 32:35; Romans 12:19; Revelation 6:9-11).

Ultimately, we agree with Joel Green, author of The Gospel of Luke, that such teaching is entirely consistent with Jesus’ fundamental goal to restore the wholeness of God’s image bearers in all aspects — spiritual, physical, and social — each expressed in the character of Jesus’ mission recorded in Luke’s Gospel account.

The point is emphasised in Luke 23:43, where even in his death, Jesus the image of God par excellence (2 Corinthians 4:4, Colossians 1:15, Hebrews 1:3) continues the redemptive ministry by petitioning for the forgiveness of his persecutors.

Clearly then, the New Testament teaches that until Christ returns at the eschaton, God is more concerned about the restoration of God’s image in humans, than bringing about retribution against those who destroy it.

To invoke capital punishment in the meantime is to deny the possibility of restoration to the wholeness of the image of God in man that has been marred by sin. By extension, it can also be argued that invoking capital punishment in the present time is sin for we are going against God’s will for the restoration of God’s image in humans.

In effect, we’re adding to sin! Indeed, with capital punishment, there will be less captives left to be set free (cf. Luke 4:18-19).

Extra-Biblical considerations

Some common arguments for capital punishment are: deterrent to serious crime, demands of justice, and protection of the innocent. These are not without their shortcomings.

Justice that promotes healing requires the offender to be held accountable for their actions. The offender must accept responsibility for the pain caused. Another essential requirement is for the victim’s loved ones to have their anguish and loss acknowledged, their anger affirmed, and their questions answered to help them deal with what happened and allow healing and restoration to take place.

On the other hand, bitter, hateful revenge has no real therapeutic value in the treatment of grief, nor does it promote social well-being in the long run. Besides, we should also acknowledge society’s share in the social maladies that spawn the crime.

To quote the 1965 General Synod of the Reformed Church in America, “A society which teaches vice through permitting pornography, glorifies crime and violence through the entertainment industry, and permits sub-standard schooling and housing through segregation has a share in the making of the offender… Capital punishment is too cheap and easy a way of absolving the guilty conscience of mankind.”

Closer to home, Amnesty International has highlighted many violations of international human rights and standards that are associated with the use of the death penalty in Malaysia.

These include lack of adequate and timely legal assistance, possibility of torture and other ill-treatment during police interrogation, the reliance on statements or information obtained without the presence of a lawyer, the presumption of guilt in cases of drug trafficking, secretive pardon processes and the extensive use of the death penalty for offences that do not meet the threshold of the “most serious crimes” or intentional killing, to which the death penalty must be restricted under international law.

On top of that, international human rights law has set rehabilitation of the offender as the goal of incarceration. This is the approach taken by Norway, a country whose incarceration rate is 60 out of every 100,000 people.

In Norway, and Scandinavian nations like Finland, 20% of adults leaving prison are reconvicted within two years of release. Compare this to the US, where 68% of people leaving prison are rearrested within 3 years of release. The main difference is that in the US, the goal of incarceration is punishment while in Norway, it is rehabilitation and restoration into society.

It is worth noting that a 2001 UK government-funded study found that restorative justice reduced the frequency of reoffending by 14%. More importantly, the majority of the victims were satisfied with the process. A separate study showed that diverting young people who committed crimes from community orders to a pre-court restorative justice process would produce lifetime cost savings of GBP 7,000 per person, and save society GBP 1 billion over a decade.

In view of these data, Christians should not support efforts that spend money, time, and effort only to seek retributive justice. Instead, the Church is better off directing its energy towards forgiveness, restitution, healing, and ultimately, restoration of God’s image to wholeness in both the offender and the victim’s family and friends.

Furthermore, the frequency at which there is a miscarriage of justice in murder cases is extremely troubling because, unlike all other judicial mistakes, it is irrevocable, wrote Marshall in Beyond Retribution. Marshall reminds us that to execute someone is to claim a God-like authority over a human life without the requisite God-like wisdom.

Indeed, Feinberg misses the point by arguing in Ethics for a Brave New World that the solution to judicial mistake is the need for more stringent regulations governing convictions in capital cases. As is the case with human fallibility, no amount of stringent regulation is going to cut it (pun intended). Let us also remember that it was Satan who deceived Adam and Eve to desire God-like wisdom and caused the fall of humanity from glory (Gen 3:1-7)!

By extension, carrying out capital punishment could be compared to the contemptuous sin of coveting God-like wisdom, on top of the arrogant sin of disregard for the sanctity of human life.

Finally, Marshall reminds us that execution entails the deliberate, carefully planned, premeditated killing of another human being, so much so that those who have supervised or carried out executions often speak of its devastating impact on them. One could say that the idea of humane execution is fantasy.

On the other side of the coin, we are faced with equally gruesome accounts of those who suffered mercilessly at the hands of murderers. This being said, callousness of the crime is in no way altered by the callousness of execution. With capital punishment, what society suffers is the nett effect in callousness. Instead, we are reminded that the bible exhorts us to overcome evil with good (Romans 12:21; cf. 1 Thessalonians 5:15 and 1 Peter 3:9).

Conclusion

Taking both Biblical and non-Biblical arguments into consideration, I am of the opinion that Christians should oppose capital punishment. The overarching theme of God’s salvation plan, from Genesis to Revelations, is about the restoration of God’s image in man, and not about retribution against those who destroy God’s image.

I recommend that Christians in Malaysia work towards the abolition of all forms of capital punishment in this country, including in the case of murder.

As the redeemed community of God’s image bearers, the Church should mediate God’s grace to both the family of the victims and also the murderer with the goal of forgiveness, restitution, healing and ultimately, restoration of God’s image in humans.

Christians should also actively advocate all forms of restorative justice over retributive justice. When we do so, may God’s will be done on earth as it is in heaven. May we overcome evil with good, while actively looking forward to Christ’s return at the eschaton to right all wrongs and bring about perfect justice.

Note: The article was originally an assignment paper written by Davin. It was then reworded for non-academic consumption with the help of a friend, Lee Chow Ping.

Read more about Davin here!